Translator’s Foreword

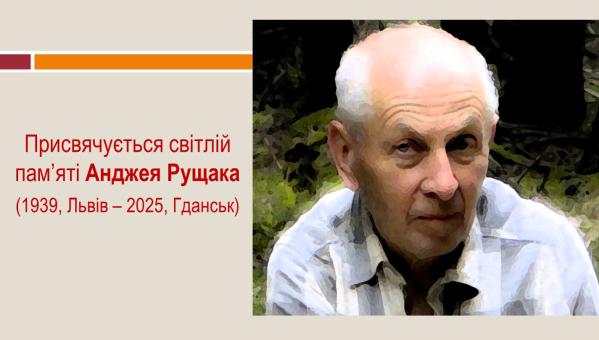

In the closing year, our colleague Andrzej Ruszczak passed away—a renowned local historian of the Hutsul region, an indefatigable traveller of mountain paths, and a passionate researcher of the figure and creative legacy of Stanisław Vincenz.

Friends from the ‘Carpathian Society’ wrote of Andrzej in an August obituary: ‘…All of the Hutsul region and all the Carpathian peaks mourn the death at the age of 86 of Andrzej Ruszczak, their most ardent admirer and true connoisseur, author of countless publications dedicated to them, particularly in the Carpathian almanac “Płaj”, a zealous researcher of the works of Stanisław Vincenz and “On the High Uplands”, and a member of the “Carpathian Society”. Always full of ideas and inspiration, and above all, consistent in their implementation—it was he who inspired us all to follow in the footsteps of the author of “Uplands”, on his escape route from the Bolshevik occupation. It was he who marked the Vincenz path in Bystrets. Farewell, Andrzej, and let the trembitas play an ancient melody for you, and let the mountain meadows carry it throughout the Hutsul Verkhovyna, which will never forget you.’

I knew Andrzej only through his numerous local history publications in the aforementioned almanac ‘Płaj’. As is known, this periodical is a printed publication dedicated to the history, ethnography, nature, and culture of the Carpathians, published by the ‘Carpathian Society’ in Warsaw twice a year from 1987 to 2020. Andrzej Ruszczak’s texts in the almanac were always distinguished by a deep insight into the subject and extreme punctuality in the presentation of information. It is, therefore, a pity that for the most part, they are unfamiliar to the Ukrainian reader.

It so happened that the first of Andrzej Ruszczak’s texts I had the opportunity to read was his study ‘The Peripeteia of Stanisław Vincenz and Jerzy Stempowski on the Hungarian Border (1939–1940)’, published in the autumn issue of ‘Płaj’ for 2007 (No. 35).

In it, Andrzej meticulously explores all the circumstances of both writers’ journey through Chornohora—a path into exile under the threat of the 1939 Bolshevik occupation. Some may perceive this text superficially, as a description of a ‘harrowing adventure’; others as a lengthy exposition of the chronology of events and a mention of many names that mean little to a contemporary. In the process of working on his research, the author consulted a vast number of sources, evidenced by an extensive list of references. But above all, he undoubtedly based it upon the autobiographical text of Vincenz himself, ‘Dialogues with the Soviets’, and on the biography of the writer by Professor Mirosława Ołdakowska-Kufel (the 2012 Ukrainian edition of which is titled ‘Stanisław Vincenz: Writer, Humanist, Advocate for the Rapprochement of Nations. A Biography’).

In his text, Andrzej points out several times that this story should not be perceived merely as a presentation of events. Both his text and, ultimately, Vincenz’s ‘Dialogues’ contain hidden mysteries and questions to which the authors attempt to find answers.

Who does Man become in the face of history’s tectonic shifts, before the collision of state systems? Where do his dignity, rights, and capacity to freely dispose of his fate disappear? Can Man refrain from surrendering his humanity in inhuman circumstances? Who is right—the one who chooses the path of armed resistance to the enemy? Or the one who offers non-violent resistance and helps his neighbour without regard for his origin or views?

Andrzej Ruszczak warned himself against over-quoting primary sources, including Vincenz’s texts, but at the same time deliberately quoted parts concerning the new, unexpected capacity of mountains to become a PLACE OF SALVATION for people threatened by tyranny. That is to say, in his vision, Chornohora acquires a quality not only of a resource useful for life—pastures and forest—nor merely of locales for admiring natural beauty, recreation, and exciting journeys. The mountains become almost the only oasis of freedom, a place in which refugees hunted by a totalitarian regime receive a chance at life: ‘Only in this gloom is there still a corner, this dark, formidable, but not so terrifying corner in the clouds, a hideout from homelessness and war, from state borders, from the influences of systems at war with one another, outside the state and above the state, as wherever Nature alone reigns.’

Let us not forget—the path through the Yablunytsya Pass, the mountain trails through Chornohora, the bridge across the Cheremosh in Kuty, or across the Dniester in Zalishchyky during the Stalinist and Nazi occupations saved the lives of many thousands of people.

The mentioned peripeteia of Stanisław Vincenz and Jerzy Stempowski were for both of them more than just an escape. They also resulted in the loss of their small homelands, the lands of their childhood. For Vincenz, it was the Hutsul region; for Stempowski—the Podolian Dniester region as well. They both clearly understood that they would not return to their native lands so long as Man was deprived of freedom there. It is not for nothing that Vincenz titled the relevant chapter of ‘Dialogues’ ‘Exodus’—in the biblical sense of the concept—and was forced to state: ‘Alas, I have lost my country as well. In the history of our corner of the world, preserved mainly in oral tradition, there is a story of a village headman in Zhabye who wrote on a stone at the entrance to his community: “Here people are trusted; this is our constitution.”’ That is, for him, the homeland—the idealistic world of childhood—combined a sense of kinship with this land and human dignity. He imagined his future life in emigration thus: ‘From now on—the flights of a sparrow, tethered by a thread.’

Therefore, the mysteries of Vincenz’s texts, touched upon by Andrzej Ruszczak in his research, appear relevant to me during this current dramatic period of our history, which we are experiencing now and will be able to survive only together.

The introduction of the Ukrainian reader to this story is, on our part, an expression of gratitude and preserved memory for a fellow who in the post-war period resided in distant Gdańsk but was in love with the Hutsul region and its people.

I conclude. At a mourners’ ‘Carpathian Meeting’ online, colleague Sławomir Czarnecki read a free-verse poem dedicated to the memory of Andrzej Ruszczak.

I have taken the liberty of translating it:

* * *

На схилі зеленої полонини

Помітив я пастиря.

Він легким кроком йшов

У бік Сонця, що заходило.

Не бачив він своїх овець, та знав,

Де вони, і котра заблукала.

Прямував до осердя Гори,

Бо старий вже був.

Плаєм широким, між смерек,

Що пахнуть життям.

Хоч не мав вже бажань,

Йшов щасливий.

Та й зник у тій Горі,

Яку так любив …

In the photo—participants of the ‘Carpathian Society’ expedition with actors of the revived Hnat Khotkevych Hutsul Theatre in the village of Krasnoyillya. Andrzej Ruszczak is standing in the second row, in front of the open doors to the museum-theatre.

* * *

The Peripeteia of Stanisław Vincenz and Jerzy Stempowski on the Hungarian Border, 1939–1940

Andrzej Ruszczak

Płaj 35

I cannot fully comprehend the words of C. G. Kiss [1] regarding the interpretation and perception of literary works, but first, I would like to quote them: ‘We already know that we should not ignore the observer. The person who is, so to speak, included in the process and becomes a participant. He loses his position as an outside observer, becoming part of the picture.’

The subject of this article seemed mysterious to me from the very beginning, and I worked on it for several years. Material accumulated, making it increasingly difficult to navigate. One February evening in 2007, I was visited by Kazio Ciechanowicz. When I began to recount fragments of these events, he became interested and said that I must write about them. In the end, I may have succeeded in uncovering some details, but the mystery remains.

There are certainly too many quotations here. For I could not follow S. Vincenz’s advice: ‘An amateur who wishes to leave a trace of his experience (…) must be careful not to sew his own book together from a hundred other books, or a treatise from a thousand quotations.’ [2]

However, it seems to me that it was also worth giving a voice directly to other authors, as this will undoubtedly resonate better with the reader. In many cases, the choice of quotations was influenced by the undeniable charm of the quoted fragments and the fear that, scattered throughout numerous publications, they might remain unnoticed. By the way, as if in passing, the quotations have created what I consider to be a rather clear picture of those days.

Let us try to capture the mood that preceded the dramatic events which soon unfolded, through an excerpt from a letter by Jerzy Stempowski [3] to Maria Dąbrowska [4].

Słoboda Rungurska, 14 September 1938

‘Dear Madam Maria,

I am returning from a several-day trip to the Carpathians (auth. — probably Chornohora). For the first time, not very satisfied. (…) Everywhere, perhaps with the exception of the wildest corners, ill winds were felt this year. Memories of the Great War have already vanished from the face of the earth and from the memories of most people. But here, for various reasons, these memories have retained a freshness unknown elsewhere. Battle sites on the mountain meadows lie untouched by ploughs, full of trenches, craters, and small fortifications in which miserable assault units burrowed under enemy fire; elsewhere, barbed wire and Spanish riders (die Spanischen Reiter) still stand, rotted but spitefully coiled with wire; the ground underfoot is strewn with cartridge cases, fragments, remains of hand grenades, tins, and iron shields with bullet dents. In one place, I even saw bones that appeared human. Not only the face of the earth but also the memory of the people has strangely well preserved the memories of those terrible years. (…) Today, under the influence of new threats, these memories have come alive, and although I have not read the newspapers all this time, on all the mountain roads I heard something like a subterranean rumble announcing the approach of bad events. Veterans of the Great War stopped me everywhere with questions as to whether a new war would really begin this year. Women asked if the soldiers who were now finishing their service, and the reservists called up for training, would really not return home but remain in their regiments. Old men crossed themselves and did not quite believe me when I tried to reassure them. We know countless sophisms that we use to ward off heavy thoughts, but the people of the land, unfamiliar with sophisms, are filled with great fear and have no peace. Their greeting, “with peace!”, has acquired immediate relevance.’ [5]

No less moving is the description of a journey undertaken by S. Vincenz and his friends on 31 August 1939. Hans Zbinden described this journey in his report ‘Polefahrt in stürmischer Zeit’ (A Journey to Poland in Stormy Times), published in the journal ‘Der Bund’ in 1939. [6]

On an ‘unforgettable day, wonderful, clear, and warm’, the group went on foot through the mountain pastures of Chornohora. During the trek, nothing significant happened. But these ‘quite small, insignificant events (…) against the background of the unshakeable peace of nature resonated so, acquired a strength that even sensational war news did not possess’. A young shepherd with three copper cauldrons, barely having offered a greeting, hurries into the valley. A moment later, a herd of sheep, goats, cows, and horses runs down. Shepherds hurry after them. Far behind hobbles an old vatah (chief shepherd). He answers the greeting in a tired voice. And instead of stopping for a long chat, as he usually did to ask for news from the world, he hobbles down, barely lifting his head, silently, as if someone were urging him on. The flocks are descending into the valley a month early, because an order was given to leave the mountain pastures. This premature departure from the meadows seems incredibly sad. What is usually a joyful and festive holiday now seems like a somber flight. Its appearance, more than news of political events, makes us painfully aware of the brutal seriousness of the moment. It is like saying goodbye to something that is ending irrevocably. Something is irrevocably destroyed, something has finished. (…) We meet a Hutsul neighbour (…), embrace, and say at the same time: “What kind of world is this, Doctor!” Our friend always said this when we told him about distant cities and countries. But how different the meaning and sound of this exclamation seem now. Then we comfort a helplessly weeping Hutsul mother whose son has been called up to the army. This consolation is brief, but in these times, is even a single day of hope not something priceless? Towards evening we reach the deserted mountain pastures. (…) Silence and devastation create a ghastly impression. A stray dog howls mournfully; its voice is lost forever in the distant, wild spaces. Again, as the sun sets (…), plunging into a sea of fire, we gaze from the Carpathian border into the forest wilderness on the Hungarian side.’

These descriptions vividly and movingly convey the atmosphere of the time and perfectly describe the area where the events that interest us unfolded.

* * *

Information regarding Stanisław Vincenz’s border crossings with Hungary between 18 September 1939 and 26/29 May 1940 is very sparse and scattered across numerous sources, often in the form of a single sentence, sometimes inaccurate, sometimes vague, and sometimes contradictory. In the work ‘Outopos’ [7], the Author recorded a condensed and, so to speak, encrypted chronological list of events related to the border crossing, noting mental abbreviations, some of which were later expanded in ‘Dialogues with the Soviets’ (henceforth in the text — ‘Dialogues’) [8].

‘Outopos’ is a ‘background’ text-notebook, not intended for publication. It contains, among other things, fragments of poems, reflections, observations, and ideas that later became separate texts. These notes were continued in Hungary at a time when ‘Soviet order’ prevailed there, from which the Author managed to extract himself with great difficulty. Therefore, some information is set out only in general terms and remains unclear to this day. It is also not explained in ‘Dialogues’, the first edition of which was published in London in 1966, at a time when the ‘institutions’ from which the writer fled were still dangerous, although the border he crossed was no longer a border between states, as after the Second World War, Chornohora fell entirely within the borders of the Soviet Union.

C. G. Kiss writes about ‘Dialogues with the Soviets’ in a work with the indicative title ‘Dialogue of a Polish Humanist with Totalitarianism’ (Stanisław Vincenz on Soviet Lust for Power): ‘I have never read such an anti-Soviet book that at the same time treated Soviet people with such warmth. (…) The Polish writer always puts the individual person at the centre of his attention. He conducts a dialogue with a person who for him is precisely a person, and not a representative of the Soviet government. (…) The aim of these conversations, as in the case of the Greek philosopher, is to find truth through successive questions (…), to empathise with the partner, and to establish principles of communication that the interlocutor can accept.’ [9]

The passage concerning the events related to the border crossing is worth quoting in full from ‘Outopos’ (pp. 74–76) to provide a basis for a broader description:

* * *

A few dates (reconstruction)

17 September. (1939) Memorable radio. The Syroyidy (Raw-eaters) approach, departure from Słoboda in the evening with Jerzy Stempowski, etc., arrival in Zhabye. Overnight stay interrupted.

18 September. Empty and surprised forests, Tatar Pass. Overnight stay in Jasiňa.

19 and 20 September. Retreat of troops, overnight stay in Rakhiv.

21 September. Beregszász.

22 September. Ungvár. (Red Cross)

23 September. Arrival at Kende [10]. Peaceful sleep. Quiet estate. Wine and grapes.

October. Budapest. Dohnányi concert — farewell to Europe and departure for Burkhut-Kvasy.

20 October. (1939) Luhy — an unexpected decision.

21 October. Chornohora and Bystrets at night. Meeting a Bolshevik: ‘Stoy, kto idyot?!’

22 October. Political commissar.

23, 24, 25 October. Zhabye (in a car and under escort through the forests near Kostrytsya) — Nadvirna. ‘Nichevo!’

27 October. Stanislaviv (four letters — in the manuscript, the words in parentheses were overwritten after the abbreviation was erased, probably — NKVD). Eternal criminals.

2 December. Sad liberation, Słoboda. Christmas marked by expulsion from home. Proof, where can I find proof? (from the German — ‘Beweise, wo find ich Beweise?’).

New Year. Zhabye, Bystrets — a lot of snow, cleared up a little.

Journey with Jędruś. January–February — Słoboda for the last time. Papa: ‘Wait a little longer.’

Bystrets, winter waits.

Wind — 19 March (1940). Sad spring.

The last time. ‘Those courtyards are sad.’ Marichka — (Lords are being abolished).

Sunday. Bystrets — 26 May (1940). A wonderful journey, until 29 May.

Luhy, 29 May (1940) The old yoke: from now on, the flights of a sparrow, tethered by a thread.

Ungvár, Záhony, Budapest, etc.

* * *

Let us now try to walk slowly along the winding paths of thought of Stanisław Vincenz, who, as Czesław Miłosz wrote, ‘takes the listener-reader by the hand, leads him in another direction, and says to him: do not look there, look here’ [11], stopping at places from which the facts described above are visible, whilst at the same time mentioning other authors who presented their point of view. I hope that ‘everyone will find different paths for themselves and see different pictures’ [12].

‘17 September (1939) Memorable radio, Syroyidy [13] approach. Departure from Słoboda in the evening with Jerzy Stempowski, etc., arrival at Zhabye. Overnight stay interrupted.’

The Author in Słoboda Rungurska (in modern times, the village of Sloboda in the Kolomyia district) listened to the radio report of the Soviet army crossing the eastern border of the Republic of Poland ‘on the memorable Sunday of 17 September’. He then recalled the advice of his fellow countrymen, mountain farmers: ‘In the event of a sudden attack on the house, flee to the nearest forest, be vigilant, watch the situation, and return when the attackers have left.’ The nearest ‘forest’ was across the Hungarian border, and he decided to head there. For now, he travelled with his eldest son (Stanisław) and two friends: a ‘renowned writer from Warsaw’ (Jerzy Stempowski) and a captain of the Polish army (Adam Miłobędzki) [14], with the intention of applying for Swiss visas and subsequently moving his family to Hungary. Before leaving, he said goodbye to his 85-year-old father, who supposedly said at that moment: ‘No, wait just another minute…’ (‘Dialogues’, p. 8).

In a letter to Jerzy Stempowski from ‘La Combe 23/07/1959’, Vincenz reminds him: ‘When we were leaving the house in the village of Słoboda to get into Miłobędzki’s car… Mr (?) forcibly pressed gold coins into my hands and advised me not to put them in my pocket in case of an attack, but to keep them in my hand.’ [15]

Jerzy Stempowski, in a letter to his father ‘Bern 27/09/1945’, describes those moments thus: ‘We decided to go into the mountains and see what was happening at the borders. From there we were to return in order to perhaps evacuate those who remained (…) So we surveyed the glorious Kuty on the day of the great exodus, and we did not like what we saw there at all. (…) So we returned to the mountains. (…) The next day we were already standing at a different border.’ [16]

Combining these two descriptions, one can with high probability determine the route they took that day: Słoboda Rungurska — Bereziv — Yabluniv — Kosiv — Kuty — Kosiv — Bukovets Pass — Kryvorivnya — Zhabye — Iltsya. They could also have travelled from Kuty through Usteryky and Yaseniv Horishniy, although this route is marked on a 1939 road map as a ‘bad, beaten path’. They likely spent the night at Leizor Hertner’s inn. Vincenz writes (‘Dialogues’, p. 9) that Leizor ‘dissuaded me from fleeing’ and that about 10 days earlier (before the invasion of Soviet troops), he had predicted this event, saying: ‘I cannot sleep at night. They will definitely come here.’

‘18. [IX.] Tatar Pass. Overnight stay in Jasiňa.’

On that day, they travelled through Zhabye (in modern times, the settlement of Verkhovyna) — Iltsya — Kryvopillya — Kryvopillya Pass — Ardzhelyuzha — Vorokhta — Tatariv — Yablunytsya to the Tatar Pass (Yablunytsya). ‘In the early morning of 18 September, we found ourselves at the Hungarian border, on the pass that has been known for centuries as the Tatar Pass (…); the weather on the gentle slopes of the pass was wonderful. (…) Private and official cars, as well as horse-drawn carriages, arrived slowly.’ There were also many peasant women from Yablunytsya and the surroundings who casually brought food for the refugees. ‘They looked at me like old acquaintances.’ The Author struck up a conversation with one of them: ‘It’s trouble, grandmother, is it not?’ She answered with a proverb: ‘Hey, sir, one trouble is like a natural mother, but seven troubles for dinner — that’s trouble.’

The group of refugees to which they belonged was likely the first to be let through, as it was only on 17 September 1939 that the Hungarians established technical conditions for crossing the border.

The crossing itself took place in conditions that did not at all resemble those of war. ‘It was still far from noon, and already at a table on the road right at the border, Hungarian officials were checking our documents. Without any brutality, without formalities, leniently and kindly, although few of us had foreign passports.’

Of the Author’s reflections on the pass, it is enough to cite two conclusions. The first seems to remain relevant even today. ‘In times when the “nation” is present, a person speaks and interacts with everyone at once, and therefore, with no one. The meeting at the pass with a sort of delegation of the nation had the advantage that the person spoke not to everyone, but to each one’ (‘Dialogues’, p. 18).

The second conclusion originally characterises the situation in Poland in September 1939: ‘We once again realised the absolutely unique situation. Two giant systems (…) merged (…) only to tear apart and stifle our land. They advanced upon it relentlessly, one like a roaring avalanche, the other like a silent glacier with a moraine beneath it’ (‘Dialogues’, pp. 19–20).

After descending from the pass, they spent the night in the town of Jasiňa (Czechoslovak Jasiňa, Hungarian Körösmezö). They were struck by the contrast: ‘Crossing the border, we seemed to regain the former mountain and pastoral time, without adventures. For on our side, on the northern side of the Carpathians, the war had torn our time apart (…). But here, on the so-called Hungarian side, a blessed silence still reigned, pastoral work prevailed, touched by nature, without any other cares but pastoral ones, just as it had been here until the day before yesterday’ (‘Dialogues’, p. 25).

Immediately after crossing the border, Vincenz sent a postcard to Hans Zbinden. It was written in German. In extremely simple but touching words, its text conveys the drama of the situation, and at the same time, these few sentences reflect the character of the Author and his assessment of those events.

‘Körösmezö at the foot of Chornohora in Hungary, 18 September.

Dear friend, under the direct threat of a Bolshevik invasion, I crossed over to Hungary with Jerzy and Stasko at the last minute. There was no other choice. All the others remained in Słoboda. Rene, the children, and their mother are in Bystrets. God knows how things will turn out for them there. I will write to you again soon and give you my address, as I am thinking about coming to Switzerland—if you could send me some money (I don’t mean just you, but all my friends, of course). In the meantime, I am contemplating the southern side of Chornohora, and for now everything is still normal, although all this is very painful, as if my skin is being flayed. I always think of you very affectionately. Sending many greetings from Stasko.’

But let us return to the Tatar Pass once more to get a fuller picture of the events, and to see how the mood and situation there had changed after a few hours. For this, we shall turn to the account of Stanisław Kaczmarski, published in ‘Wieści Polskie’ in 1944. [17]

Civilian refugees and Polish military personnel at the Yablunytsya Pass near the village of Lazeshchyna on 18 September 1939.

In the evening (18 September), darkness fell and a fine, piercing rain began. ‘Two trucks, the remains of our group, stand in the middle of a huge snake consisting of thousands of motor vehicles of all kinds, as well as cannons and horse-drawn carriages. The narrow road can barely accommodate two rows. People on foot or on bicycles pick their way forward.’ A mood of panic and uncertainty prevailed, fueled by rumours. The next morning, the weather was sunny. ‘We didn't even notice when we drove up to the border. The cars moved very slowly, as the processing of our arrival at the border was underway. We all breathed a sigh of relief.’ From another report we learn that on the Hungarian side of the pass there was a watchtower, and next to it, on a tall mast, the red-white-green Hungarian flag flew, visible from afar.

‘19th and 20th [IX.] Retreat of troops, overnight stay in Rakhiv.’

In ‘Dialogues’ (p. 26), the Author notes: ‘We were overtaken and pushed back by large units—several thousand Polish soldiers, a sort of reserve, equipped with tanks and well-armed. (…) Cut off by the Russian invasion, they retreated by order (…) without engaging in battle.’ In fact, this was the mechanized 10th Cavalry Brigade under the command of Colonel Stanisław Maczek, which crossed the border after heavy fighting near Lviv.

‘21 September, Beregszász. 22 September, Ungvár. Red Cross’

These were towns in what was then eastern Hungary, today in Ukrainian Transcarpathia, through which the railway evacuation route for Polish refugees passed. In Ungvár (Uzhhorod), there was a Polish consulate, and the refugees were accommodated in a Basilian monastery.

‘23 September. Arrival at the Kende estate (A Dream of Peace). Quiet estate. Wine and grapes.’ ‘October. Budapest. Dohnányi concert — farewell to Europe and departure for Burkhut-Kvasy.’

‘A Dream of Peace’ is the title of one of the chapters in ‘Dialogues’ (pp. 25–44). Kende is the surname of the family of landowners who hosted the refugees for several days. Jerzy Stempowski (‘Letters’, p. 112) wrote, demonstrating a tendency toward dramatisation of the situation (as we shall also see later): ‘For some time, under threat of arrest, we hid in the countryside with an old nobleman, where life was more or less the same as in our grandfather’s youth.’

For the Author, the month-long stay in Hungary reminded him of Bruegel the Elder’s painting from the Munich Pinakothek titled *Schlaraffenland* (The Land of Cockaigne): ‘A soldier, a writer, and a peasant lie on the ground, intoxicated by consumption, and around them is a world formed for this consumption: fences made of sausages. But among all these wonders, only one thing was lacking: there was no way to know what was happening at home, on the northern side of the Carpathians’ (‘Dialogues’, p. 29).

In Budapest, the refugees legalised their stay. Turning to friends in Switzerland and England, they received funds and instructions to consulates. They were advised to ‘get visas and return as soon as possible’. However, Vincenz could not postpone the moving of his family. During his stay in Budapest, he visited the Városliget art gallery, private collections of East Asian art, and the ethnographic museum, where he was particularly interested in an exhibition dedicated to steppe livestock farming. He also visited the ancient Roman settlement of Aquincum on the right bank of the Danube near Budapest. The last evening before departing for the border, he spent at the Philharmonic, attending a concert by the world-famous Hungarian pianist and musician Ernst von Dohnányi. And this was his ‘farewell to Europe’. There was no time to delay the return to the mountains, ‘autumn was approaching; we knew that the mountains were no joke, and in a week it might be too late.’ As subsequent descriptions testify, three people set out for the border: Vincenz with his son and Jerzy Stempowski.

In ‘Dialogues’ (p. 52), the Author recalls how his comrade, the legionnaire-captain, ‘pushed a pistol onto his son — and a particularly trendy one at that’, to which he himself objected: ‘I knew that it would never be of any use and might even cause unnecessary harm.’ This incident likely occurred in Budapest.

They took a train to the second-to-last railway station before the border, Burkhut-Kvasy in the valley of the Black Tysa, where they arrived in wonderful weather. ‘There was no news or rumours from the Polish side. (…) Now one country had ceased to exist for the other. (…) The border was best guarded (…) by the fear of the unknown.’

They spent the night in a manor house belonging to the widow of a Magyarised Jew. Their initial intention was to ‘find someone reliable who could be sent to their families, either to reach an understanding or perhaps even to help them get to Hungary. (…) At first, we wanted to achieve contact with the village just across the border on the Polish side, where I had a summer house (meaning Bystrets), where part of my family had been until recently, although I was not sure of that at the time’ (‘Dialogues’, p. 40). Despite their efforts, the lady of the house could not find anyone willing to undertake this mission.

The author's son remained at the estate waiting for news, whilst Vincenz and Stempowski arrived on an evening, overcrowded bus at the last hamlet near the border—Luhy in the White Tysa valley. When the standing passengers got off at the penultimate stop, Stempowski saw an elegant and beautiful woman dressed in city clothes. Her appearance was sad, like death in the form of a young woman. As it later turned out, this was Cilly, the daughter of the estate owner. And although she served wine and cheese with a smile, the expression in her eyes remained unchanged; ‘she retained a distressed look in which some misfortune was hidden’. [18]

Local Jews advised them to seek help from the old patriarch of smugglers, who ‘knew everything and could do everything, and was himself the embodiment of reliability’. His dwelling, with its numerous farm outbuildings at the foot of a steep slope, was like ‘a real castle for smugglers. (…) Even from afar it was obvious that the very steep descent from the Polish side, wavy with bends, hid the path so carefully that anyone descending from the mountain to the manor was invisible until the last moment. The bearded and elderly patriarch of smugglers, originally from Galicia, received us kindly and with understanding’ (‘Dialogues’, p. 41).

Stempowski describes the innkeeper thus (‘Letters’, p. 132): ‘There we met the king of the local smugglers, who looked like Paul Kruger, the president of the Transvaal. Interestingly, his son at that time had a doctorate in philosophy from the University of Prague.’

This man explored the possibilities of crossing the border for ‘professionals’ who could either bring news to Vincenz about his family or lead them there. However, this time, too, it was to no avail. Stempowski describes the location of the smuggler's inn in Luhy quite accurately, describing the house where he spent the winter: ‘On the bank of the White Tysa river, less than a kilometre below the inn, stood the only brick house in the area with four rooms. In the time of Czech rule, it had housed a gendarme station, then a tourist hostel. For several years the house had stood abandoned.’ [19]

Stempowski also later describes the further wartime fate of the smugglers' headquarters: ‘As far as I know, the estate was subsequently looted many times, and the residents either died a violent death or were scattered across the whole world.’ [20]

Vincenz wrote about his plans for crossing the border in ‘Dialogues’ (pp. 41–42): ‘I had not yet made a decision, but I was close to it, for it seemed to me that there was nothing easier than to cross the mountain range to the other side, simply from village to village. (…) Friends and visas were waiting. (…) That is why we made quite detailed plans for our return, in case I went alone on foot. (…) We surveyed the area. (…) We climbed quite high along empty paths. On the high pastures there was no more livestock; everywhere was deserted. (…) We could see as if in the palm of our hand the peaks, cliffs, passes, and even mountain huts under the heights… We had to hurry, hurry! For a single wind could turn the country into something like a polar kingdom.’ One such day, 18 October, is described by Stempowski in ‘Notes for a Phantom’ (p. 60): ‘For the last time I climbed the forested Munchel (Mentsil 1592 m) to mark landmarks for crossing the forest border on an old Austrian map.’ [21]

‘Luhy — an unexpected decision, 20 October 1939.’

The decision was made by chance. The author’s son arrived unexpectedly by bus from Burkhut-Kvasy with the news that parts of the Soviet army had retreated and the border was unguarded. Therefore, they decided to cross the border the next morning to reach Bystrets, and then either send someone or go themselves to the Vincenz family home in Słoboda Rungurska: ‘We still had a truly brave desire to return, even on a stretcher, a critically ill person for whom we all cared very much.’ It is quite likely that this refers to Ludwika Rettinger, a friend of Jerzy Stempowski, who remained in Słoboda Rungurska, sick with breast cancer, and had already died by that time. ‘We determined once again when we would likely return and when (Jerzy Stempowski) should expect us, whether at the “patriarch's” estate or even a little higher, on one of the paths. But these plans, (…) as it soon turned out, were too optimistic’ (‘Dialogues’, p. 44).

In a letter to Stempowski, Vincenz retrospectively evaluates the situation: ‘My biggest mistake was that I underestimated the distance from Luhy to Bystrets; that is, I estimated it based on the condition of my legs, lungs, and heart at the age of 23, when at that moment I was already 51. (…) I also neglected your warning to go through ravines and not paths after reaching Bystrets, especially near the house. (…) Stasko felt very sorry for me when I tried to follow this rule.’ [22]

‘21 October. Chornohora and Bystrets at night. Meeting a Bolshevik.’

The chapter of ‘Dialogues’ describing these events is titled ‘Paradise Regained’, and the date of their departure toward the border is given as 20 October. The Author and his son were accompanied as a guide by Olenka, a no longer young shepherdess recommended by the ‘patriarch’. Jerzy Stempowski also accompanied them as far as the bridge across the stream. They set out from Luhy at dawn.

In ‘Notes for a Phantom’ (pp. 60–61), Stempowski describes their farewell: ‘I stopped on the bridge to observe Doctor Vincenz, who was hurriedly climbing the slope of Ryza. In this haste there was something sinister. His head wobbled on his shoulders like a doll on strings. These strange movements gave me a particular vision. Vincenz seemed wrinkled and pale, with a large head that barely held onto a thin, shaky neck. Agitated by this vision, I still hoped that he would turn around, and that I would be able to see his face one more time. But he did not turn around. He raced toward his doom.’

Meanwhile, Vincenz describes the moment of farewell thus: ‘My friend was so moved that, although he was considered a nihilist, he passionately exclaimed: “Beloved Mr Stanisław, may God guide you!” (…) I immediately became uneasy; I thought, perhaps superstitiously: “Oh, it is not right for an atheist to bless in the name of God.” But in the meantime we were moving our legs briskly, constantly uphill, via an ever shorter route, higher and higher. We were already on a steep, forested ridge when we heard from below the sound of a bus engine being started, which departed after six in the morning for Burkhut-Kvasy station (on which Stempowski travelled). Now everything was cut off from that world! For how long? (…) That farewell roar of the engine filled me with sadness’ (‘Dialogues’, p. 45).

Around eleven o'clock they climbed above the upper timberline. Then ‘there appeared from up close slopes with cliffs (…), peaks covered in thick clouds.’ The wind kept increasing, turning into a hurricane near Lake Tomnatsky (Lake Brebeneskul). They climbed the steep slopes of Brebeneskul; beneath their feet was a dark, deep whirlwind of mist. Vincenz recalled: ‘Although I exerted myself as much as I could, carrying my nearly 90 kilograms of live weight, and although my son and Olenka zealously pushed me from behind, the ascent was difficult and quite slow.’

The border ridge here forms a long, wide hollow between the peaks of Kedrovaty-Pohorilka (marker 26) in the east and Gutyn Tomnatyk (marker 28) in the west. The southern slope here is very steep and grassy, and it was along it that the ascent continued. Thus, they reached the ridge, probably between border posts 25/6 and 26/2, or 27/4 and 27/5 of the former Polish-Czechoslovak border—from March 1939, the Polish-Hungarian border—and from the time of the Red Army's occupation of Pokuttya, the border between Hungary and the Soviet Union. They walked along the ridge to the left, toward the west, looking for a safe descent to the north.

‘But although the ground beneath our feet was fairly level and firm, we moved extremely slowly (…), holding hands (…), for the wind nearly knocked us off our feet, and with each stronger blast we hastily lay on our bellies. (…) We searched for the way more with our feet and mind than with our eyes. (…) We walked for a long time, (…) meanwhile the slope of the ridge slowly but steadily rose. Slowly, to the right, it brightened a little; before us emerged no longer precipices filled with clouds, but rock ribs and bizarre sandstone towers. At a certain point we saw on the right some kind of rock corridor, as if the bed of a dried-up stream. Still in the mist, but a little cleared, we descended, initially as a test, through this corridor, since it was protected by rocks on both sides. We fared well, heading constantly downwards to the north, and at about four o'clock in the afternoon we emerged from the clouds. A gentle sun, as if tired, illuminated the wide golden slopes, and the mountains, shimmering with sparkles, were unrecognisable. Everything was so changed that something almost pulled us back upward. After some hesitation, even after a brief alarm that we were lost, we realised: yes, this was our paradise, finally regained. The pastures and forests, motionless and silent, seemed very sad to us—perhaps because, like spring, which in our mountains rises slowly in many quiet joys, so autumn grieves long and painfully until everything is covered by unexpected, heavy snow (…) For although only a few hours ago, forgetting everything—about borders, politics, and war—we yearned only for one thing: to escape from this cold wasteland, from this cold, diabolical swing of black wind; yet when we found the light, we suddenly realised that only in this gloom is there still a corner, this dark, formidable, but not so terrifying corner in the clouds, a hideout from homelessness and war, from state borders, from the influences of systems at war with one another, outside the state and above the state, as wherever Nature alone reigns. (‘Dialogues’, pp. 48–50).

Based on this general description, one might attempt to reconstruct the likely crossing route. Although the author does not mention any ascents since reaching the ridge, they must have climbed to the top of Gutyn Tomnatyk, where boundary marker 28 stands. Here, the ridge turns north. It is difficult to imagine that in the fog they decided to leave the ridge path and traverse, bypassing the peak of Rebra (2001 m) with marker 29 and the peak of Shpytsi (1935 m). Moreover, Vincenz mentions twice that they walked along the ridge itself. Thus, a gentle ascent to Rebra awaited them, then a descent to a pass and a gentle climb to the top of Shpytsi marked with number 30.

Here it is important to turn to the description given in the Biography (p. 195): “They reached the vicinity of a peak named Rebra, or even passed it, as the author noted characteristic rib-like rocks which they passed (…). Finally, they found a stone corridor to the right that allowed them to descend from the ridge.”

However, the “stone ribs” of Rebra are not visible from above on the eastern slope. Descent here is impossible due to the steepness—the slope forms an almost vertical hollow bordering a glacial basin. One could descend along the ridge from marker 29 towards the north-east, but in “Dialogues” (p. 49) there is no mention of any “stone corridors”. Thus, after marker 30, the travellers had to leave the border ridge and head north-east towards the Shpytsi ridge, which, according to the author, descended slowly. On its south-eastern slope are rows of sharp ribs and rock spires, famous for their unique landscapes. These form the “corridors”, and it is likely they found a passage in one of them. The slope here is grassy, though very steep.

They then descended to the upper Gadzhyna basin, from where a path begins that leads to Bystrets. Further on, crossing the slopes, they approached “the intersection of shepherd paths where Polish border guards used to stand watch (…). It was already completely dark when we descended to a steep ravine, to a rushing river, on the opposite bank of which stood our house.”

This was the spot where the first “dialogue with a Soviet” occurred, in which the author, thanks to his ability to speak with anyone and his magic of trust and humour, was able to get out of trouble. In the near future, he would experience many more such complex situations. He always knew how to conduct a dialogue such that the interlocutor treated him with trust and looked upon him with thinly veiled admiration. In a letter to the author dated 5 March 1970, after reading “Dialogues with the Soviets”, Zbigniew Herbert wrote: “I would like to sincerely thank you—as a faithful reader—for this beautiful, human conversation (…). It seems to me that I have managed to draw a little from your wisdom.” [23]

In the mountains of Dauphiné, Jeanne Hersch noticed this extraordinary ability of Stanisław Vincenz to strike up a conversation with anyone: “The peasants came to sit with him and talk whenever they had a free moment, at any time of day (…). He would leave the texts of Homer, Shakespeare, or Dante (…) and devote himself entirely to those around him (…) They came because with him, under his gaze (…) they felt recognized as they truly were, that they were beginning to be who they are.” [24]

Joanna Tokarska-Bakir also emphasises Vincenz’s extraordinary ability to speak with anyone: “From a phantom, a semi-wild stateless people, he extracted—by methods known only to himself—who they really were: simple village lads who flocked to the ‘Professor’ because he reminded them of something distant, of something they had been deprived of.”

During stops with friends in Hutsul hamlets and villages, we have repeatedly seen how easy it is to strike up a friendly conversation by applying the wisdom of Stanisław Vincenz. And how applicable this wisdom is to conversations between Poles and their neighbours across the eastern border.

Having written the above, I wondered if I had the right to express such an opinion. But in a letter from Konstanty A. Jeleński to Andrzej Vincenz dated 16 February 1980, I found this thought on the work of Stanisław Vincenz: “I am struck by the extent to which Mr Stanisław’s work, thought, and personality are becoming increasingly modern (in the sense that they are becoming an increasingly necessary lesson in the dead ends of our time).” [25]

Let us return to the headwaters of the Bystrets river, where that first encounter with Soviet soldiers took place: “The night was indeed clear, but it was completely dark in the ravine; not a movement or a sound was to be heard on the paths, so we ventured to descend the winding trail, even shining an electric torch here and there. Although I remembered again at the last moment that we should first go to a friendly neighbour, we nonetheless, at a run and with a sense of security on such a familiar path, approached our estate. Then, reaching the hedge and the spruce grove, we heard a voice from the dark thicket: ‘Stoy! Kto idyot?!’. Not knowing why, perhaps to ease the tension, I jokingly replied, as if proving I was not afraid: ‘Matarzhuk (that was the neighbour’s name), do not pretend to be the Red Army and come out of the woods, it is I.’ The same voice replied: ‘Nyet, eto Krasnaya armiya!’ Then a line of dark, armed figures surrounded us. Then, again under some impulse, I walked up to the first figure (…) and held out my hand: ‘It is I, from this house, I am going home.’ (…) The young patrol leader effectively allowed himself to be disarmed (…). He was as if mesmerised by the surprise. ‘Are you that writer who lives in this house? We heard you were in Hungary. Your family lives here peacefully; we do not harm such people.’”

The ensuing conversation created the impression of a meeting between good friends, after which they said a pleasant farewell. “We left with great relief, and a few minutes later (after 21:00) we were home, to the great amazement of the family, stunned by this surprise” (“Dialogues”, pp. 51–52). Irena Vincenz commented years later: “The beloved madman came to save us, and ended up in prison himself.”

As it later turned out, they were stopped by a border service patrol. Regular troops had retreated from the border a few days earlier. The border guards were especially vigilant at night, and the Vincenz house in Bystrets was under constant surveillance.

Jerzy Stempowski presents several versions of what happened at the border. In the “Letters” (p. 132), in the previously cited letter to his father dated 27 September 1945, he describes these events in a few sentences: “Vincenz and his son were the first to cross the northern slope [over the border], where they were caught by the first patrol to go into the mountains, and they vanished from my sight for many months. I followed them, wishing to walk 130 km to Słoboda along the mountain peaks (…). On the way, I caught pneumonia at a spot 20 hours’ walk from the last smugglers’ refuge, spending the night in a bear’s den. There was no point in returning there, and I decided to descend to the Black Tysa at Burkhut (Kvasy). To do this, I had to walk 73 km along the mountain tops (…). Delirious with fever, I walked for two and a half days (…), wrapping myself in a sleeping bag every few hours, but sleep did not come (…). In the smugglers’ inn I lay for several days, packed with hot bricks.”

In the absence of improvement, he was transferred to a small hospital 7 km further down, built by the Czechs for forestry workers. There he remained from 29 October to 2 January 1940. He then returned to the “smugglers’ inn” and spent the rest of the winter there. Ultimately, he learned of the situation in the country and realised there was no point in waiting at the border. He then set off for Budapest, where he spent a few more weeks—this time in an impeccable hospital.

In a letter to Zygmunt Haupt dated 11 January 1966 [26], Stempowski recalls his last stay in the Eastern Carpathians at the end of October 1939, while waiting for the return of S. Vincenz with his family: “I left the ‘Kamiela’ inn in Bohdan-Luhy, near the sources of the White Tysa, climbed Gutyn Tomnatyk, spent the night in a bear’s den, and then, along the southern slope of Chornohora and Petros, descended to the Sheshul mountain pasture and through the forest to Burkhut-Kvasy on the Black Tysa (…). I walked alone, mostly at night under a full moon, struggling with the onset of pneumonia.”

In a letter dated 24 January 1940 to Bolesław Miciński and his wife Halina Kenarowa, Stempowski writes of the same events: “I crossed the border early, a day ahead of the Soviet troops. Since then, various incidents kept me in the mountains near the border. This time the mountains brought me no good. Here I lost my last companion, Doctor Vincenz, who was seized by a Soviet patrol almost before my eyes when we were trying to smuggle his younger children across the border. Only much later did I learn that he was alive and free.” Not surprisingly, as Halina Kenarowa recalls, “in several places the green ink ran with the stains of our tears.”

In a postcard to Janina Orunshyna received in the winter of 1939/40, Stempowski reported that “after an attack of helplessness, he woke up in a small hospital on the Hungarian side, buried in snow, in absolute solitude and despair, and begged for the smallest sign of life.” She did not know how to help him. She was advised to turn to the Freemasons. Using these connections, she informed Marian Ponikiewski, who was responsible for helping Poles in Hungary, and who promised to send a team of students to collect J. Stempowski, “as soon as the snows, unusually heavy this winter, become passable.” A few months later, he wrote a more cheerful letter from a respectable hospital in Budapest. [27]

However, in a conversation with Janina Orunshyna in a café in Bern, Stempowski gave yet another version of these events, combining facts that occurred before the border crossing with those that occurred later when he was already in Hungary. Here is her account: “Driven by fear of the approaching barbarians, one day he set off into the mountains to test the paths to the green border (…). On the way, however, he was overtaken by an unexpected attack of paralysis. When he woke, he was lying in a cave of smugglers, who had found him helpless in the mountains. Every mountaineer who wanders alone is a citizen of the world, for he meets every lonely person with kindness. The smugglers placed him on a sack of beech leaves (…). He was completely helpless and had to lie with the smugglers until he could get back on his feet. The smugglers led him with them into the mountains (…), via their own route. And he again lost consciousness and came to his senses only in a small hospital, as it turned out, on the Hungarian side.” [28]

Stempowski’s provided accounts may cover the period from 20 October, when he parted with Vincenz, to 28 October, the date he was hospitalised in the “mountain hospital”. Based on this, it is very difficult to form an opinion on these seemingly surreal events. However, as the previously cited letter from Vincenz to Stempowski shows, these actions were planned in advance and may indeed have taken place: “Another manifestation of your adventures, as understated as the others, was the memory of how you searched for us in Chornohora and spent the night in a bear’s den.”

Let us return to Bystrets where, having come home in the evening, Vincenz was faced with a choice: “either flee back to Hungary that same night with his family, who were completely unprepared (…), or go that same night to Słoboda to mobilise the rest of the family, or finally, to stay put (…). But the last option was not only the most sensible but effectively the only one possible, especially as I was so exhausted that, once seated, I could barely move” (“Dialogues”, p. 54).

22 October. “Politruk”.

The following morning, the author was visited at his home by a “politruk” (political commissar) from the border post in Bystrets, accompanied by an armed senior officer. The politruk “noted with regret that we should have presented ourselves honestly at the post last night, for the Soviet Union must be trusted, and all citizens trust the Soviet government (…). Finally, he told me that my son and I must go to the post in order to—‘pagavarit’ (talk) (…). In hundreds of stories later I heard this same word as a prelude to negotiations, or rather, very long investigations. As the politruk assured me, we were to return by lunch…” (“Dialogues”, p. 57).

The author describes in simple language the dramatic moment of being led from the house. However, the Hutsul neighbours were able to appreciate the seriousness of the situation, for as he continues: “We had barely gone two hundred paces when we were overtaken by one of the neighbours, a poor and quite old cottager named Petrusko, who often worked for us. Catching up, he shouted: ‘Sirs, Soviets, let this man go; he is no bourgeois, he is a man of the people! I tell you, I beg you, I am poor, and I know him well!’ He repeated this several times, stubbornly and pleadingly, and it was not only his friendship with me, but a sign of his trust in the Soviet authorities, that a poor man could achieve something, according to the propaganda that was constantly spread.” The politruk showed no irritation. “I was somewhat moved by Petrusko’s intervention, and even more surprised at how quickly he found out and was already waiting for us. I said goodbye to him, and he watched us sorrowfully.” [29]

This scene was undoubtedly an alarming and shocking experience for Vincenz’s neighbours. It must have become the subject of many stories later, as it remained vivid in the memory of Vasyl Bilyloholovyy, who was probably about seven years old at the time. The late Ivan Kikunchuk, the last herbalist in Bystrets, also spoke with great emotion about how Stanisław Vincenz was brought to the guard post. The post was about 40 minutes’ walk from the writer’s house. It probably stood near where the shop is now located. Traces of the stone foundation remain.

The guard post was the site of the Vincenz family’s first interrogation and their first night spent there as prisoners. When the author was asked about the circumstances of their border crossing, he said that “he came to visit his family because he learned there were no Germans here, but only Soviet troops.” He did not reveal the route of his crossing, but said that they had crossed the easily accessible route from Jasiňa to Yablunytsya. They slept in a changing room on very uncomfortable beds brought from a nearby warehouse (“Dialogues”, p. 59).

23 – 25. X. Zhabye – Nadvirna (by car under escort through the forests near Kostrytsya).

The following day, the prisoners were escorted on foot to Iltsya, a suburb of Zhabye, to the building of the Hutsul Museum, which at that time housed a company of border guards [30] (“Dialogues”, p. 62). “Ahead of us walked an under-officer with an English light machine gun, ready to fire, and behind us also soldiers with weapons at the ready.” This convoy made an unpleasant impression on the local residents, who, recognising Vincenz, ceased their loud talking and only whispered quietly among themselves. The detainees were placed in an office which also served as a cell for prisoners. They were brought comfortable beds and a good lunch.

They were held here “for a long time” (“Dialogues”, p. 70). Chronology shows they slept there for two nights. Although promises of release had been made, one morning: “It was depressing when we were driven in a truck away from our little homeland. The road we took reminded us of happy journeys with our French friend Christian Sénéchal and his family a few years ago. [31] At one point we drove close to the ridge behind which lay my home.” [32].

The route passed through Kryvopillya, the pass, Vorokhta, Tatariv, Mykulychyn, Yamna, Yaremche, Dora, and Deliatyn. In “Dialogues” (pp. 71–72), the Author describes his impressions of this journey: “On the way I saw the resort areas on the Prut river, well known throughout the country (…). They were full of red flags hanging from buildings, and posters scattered everywhere. The first sign of Soviet occupation in this undeniable ugliness. But, apart from military quarters, the villas and guest houses stood uninhabited, boarded up, windowless, with doors torn off, empty of furniture. Along the road in several places, teenagers around bonfires enthusiastically cheered our escort, which was a characteristic custom of the idyllic period of that time. The impression of the journey was sad (…). Elderly peasants wandered quietly, sleepily, worriedly, or listlessly. It is unknown what led them to such a mood, whether it was the absence of guests or perhaps the uncertainty of tomorrow, which began with the disastrous exchange rate of currencies, then the chaos in prices and the shortage of goods.”

After a few hours, they arrived at the judicial detention centre in Nadvirna, “subordinated to the command of the battalion already stationed there as a link to the infamous NKVD institution.”

27 October, Stanislaviv (four letters, possibly NKVD). “Eternal criminals.” [33]

That day all detainees were moved. First by truck to the railway station in Nadvirna, then at night by train to Stanislaviv. They arrived in the morning. The prisoners were formed into military ranks. Guards with fixed bayonets surrounded them and led them through the streets. “We passed by a Polish gymnasium, and a crowd of girls, students, peered out from the windows, watching us at first with curiosity and serenity, then with genuine horror. Suddenly one of them burst into tears, then one after another they sobbed loudly” (“Dialogues”, p. 83).

Finally, they reached the prison building next to the district court. “The gate opened and we entered the gates of the NKVD.” They spent about seven weeks in the prison.

2 December. Sad liberation, Słoboda. Christmas marked by expulsion from home. “Proof, where can I find proof?” (from the German – “Beweise, wo find ich Beweise?”). [34]

In “Dialogues” (p. 144) the date of return from the prison in Stanislaviv to the house in Słoboda is given as 4 December. The circumstances preceding their release are described in the chapters “Farewell”, “Return”, and “Our Benefactors”.

The Author’s first wife, Lena, who knew the Russian milieu well, initiated persistent efforts for his release. [35] “She was able to encourage (…) in particular, some of the Ukrainians and Jews to follow the case, for they could still dare to appeal to the Soviet authorities, whereas for the Poles it was more difficult as the so-called ‘masters’ feared to harm me” (“Dialogues”, pp. 146–147).

Soon the prisoners felt their situation changing: “The situation (…) soon improved, as first we were brought warm coats from home, and two days later we received a generous food parcel. We confirmed receipt with our own signatures, and this was exceptionally valuable for our family, as even the border guards from our post in Bystrets expressed a suspicion that we were already in Kyiv” (“Dialogues”, p. 130).

Shortly after this, the Vincenzes were summoned for questioning by a judge, who stated: “Everything has been checked; a very important Soviet writer will come here to ‘philosophise’ with you.” Later, the author and his son visited a prosecutor who, after reviewing the cases, decided to release them. They continued to answer questions before “something like a collegium.”

The next day they were issued release certificates without the right to live in major cities. Later, they were taken to the regional party committee, which was located in a hotel, where they met the “chairman” of the regional committee himself, who told the author that “he was much needed, for literature must be organised immediately.”

On 4 December 1939, they were provided with a car. “It carried some sort of pass that allowed it to go anywhere. The driver was an Armenian from Kuty. My first impulse, like a wild animal breaking out of a cage, was—to run! I wanted to go immediately to the border and cross straight into Hungary (…). Having calmed down as much as possible, I restrained that foolish urge to flee immediately and decided that we would go nonetheless to our family estate in Słoboda Rungurska” (“Dialogues”, p. 144).

“It was already dusk when we arrived at the house (…). Some unknown young men were walking carefully across the footbridge over the stream. It turned out these were disguised Polish soldiers escaping to Hungary who had chosen our house as a transfer point. [36] Meanwhile, the appearance of the car near our house caused a commotion, as private cars no longer existed, only official ones, so this caused fear (…). At home everything was as usual; the telephone had not yet been taken, and the radio was broadcasting BBC news in Polish” (“Dialogues”, pp. 144–145).

In the evening the Author urged the family to cross the border as soon as possible to go to Switzerland, where friends were waiting. “However, we encountered lack of preparation and strong resistance.” The border peaks were covered in deep snow, and Vincenz himself noted of his health: “I was exhausted and, as it seemed to me, even ill” (“Dialogues”, pp. 144–146).

What was the decisive factor in his release from prison? Today it is difficult to determine definitively. Certainly many factors contributed. It is known that Vincenz’s first wife used her connections with Russian and Ukrainian writers, informing them of the arrest of her husband, who was already well known in Ukrainian literary circles at the time. Volodymyr Polek lists the names of these writers. [37] They were: Petro Kozlanyuk, an admirer of Vincenz’s pastoral works [38], Ivan Le, mentioned in “Dialogues” as “Comrade Z” [39], and Yurii Yanovsky [40]. Besides a garbled name Ivan Fre, Andrzej Vincenz also mentions Petro Panch [41].

Polek quotes a letter from Ivan Le (dated April 1967), one of the founders of the Lviv branch of the Writers’ Union of Ukraine, in which he describes in very general terms the steps he took to help S. Vincenz. Initially, he decided to seek advice from “authoritative” circles. He was advised that the Writers’ Union should establish contact with Vincenz and try to bring him closer to the circle of Soviet writers in Lviv. Le continues: “Therefore, we, as the Writers’ Union, wrote a written guarantee for the imprisoned writer (…). Petro Kozlanyuk and I managed to go and release Vincenz from his plight (…). We extracted him from that unpleasant situation and took him all the way home to the mountains.” The information in Ivan Le’s letter is likely incomplete due to the political situation (in 1967 Nikita Khrushchev was still alive, who had held the post of First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine from 1938 to 1949). Furthermore, the subsequent departure of S. Vincenz for Hungary likely placed his guarantors in a difficult position.

“Comrade Z” allegedly later visited Vincenz at his home in Słoboda Rungurska. This was in mid-December 1939.

Vincenz himself denies a visit by “Comrade Z” (“Dialogues”, p. 153): “I never met my benefactor, Comrade Z, again. A few months later, in the spring, he sent me a translation of his book, not by post but through an acquaintance. He gave no address and wrote no letters.”

According to Polek, notes and correspondence with Vincenz were allegedly in Ivan Le’s possession, but were lost during the war.

At that same time, the Jewish poet Ber Horovyts [42] brought several Ukrainian writers from Kyiv with him [43]. This visit is described in detail in “Dialogues” (pp. 149–152).

A few days after the Author’s release, lawyer friends from a nearby town informed him of the legal aspect of his release: “You are a rare beneficiary due to the absence of the rule of law, namely a system based on the principle that the sentence must be beneficial to the state. According to the penal code, you should have received six months’ imprisonment or more, but it was thought that your release would be more beneficial. Be happy with that; others will already have served for you.” [43].

Słoboda. Christmas marked by eviction from the house.

As Ołdakowska-Kufel reports (Biography, p. 206), this entry can be linked to the looting by the Soviet authorities of the Writer’s house in Słoboda Rungurska, when valuable furniture and an entire large library were removed in trucks.

New Year, Zhabye, Bystrets. Lots of snow, a little brighter.

Stanisław Vincenz’s cottage in Bystrets, 1927.

Journey with Jędruś. January – February – Słoboda for the last time.

Jędruś is the Author’s younger son, Andrzej. They then travelled by sleigh from Bystrets to Słoboda Rungurska.

Papa: “Wait a little longer.” Bystrets, winter waiting.”

According to the text of “Dialogues” (p. 8), a sentence similar to this: “No, wait just another minute”, was said by the Author’s father during their first farewell on 17 September 1939. The words “winter waiting” refer to the wait for the snow to melt and the possibility of crossing the border.

“Wind – 19 March [1940] Sad spring.”

On that day, Stanisław Vincenz’s sons, Andrzej, then 17, and Stanisław, 24, left home and began their ski journey across Chornohora to Hungary. This early departure was caused by the fear of being drafted into the Red Army, which was expected at any moment. Two Hutsul guides escorted the boys to the border. They spent the night in a shepherd’s hut, and around it, the guides laid numerous false paths branching in different directions to confuse Soviet border guard patrols (according to Mirosława Ołdakowska-Kufel’s account of her conversation with Andrzej Vincenz). The Biography (pp. 208–209) tells of their adventures on the Hungarian side: how they got lost, came across wolf tracks, met a Hungarian border guard, and fled across the Tysa river. Eventually they reached Budapest.

J. Stempowski mentions this in a letter to his father: “Finally, two of Vincenz’s sons arrived. I sent the younger one [Andrzej] to the West and kept the older one [Stanisław], his mother’s only son, with me, waiting for her arrival after the snow melts.” (Letters, p. 135).

Later, Andrzej fought in the battles as part of General Maczek’s 1st Armoured Division.

“For the last time. Marichka: ‘Those courtyards are somewhat sad. Lords are being abolished.’”

The Author cites these words in “Dialogues” (p. 174) in the phrasing: “That house is somewhat very sad.” They were said by an 80-year-old neighbour when they were preparing to leave their home [44].

News reaching Bystrets indicated that “increasingly harsh unification would occur (…). Every settlement (…) would be closely surrounded, and our stay in the mountains, especially near the border, would become a glaring, unbearable, and possibly dangerous anachronism.” Preparation for crossing the border had thus been underway for a long time (an account by Barbara Vincenz and Helena Łuczyńska on this matter is given in the Biography, pp. 207–208), but the northern side of the mountain ridge was still too snowy. According to information from M. Ołdakowska-Kufel (Biography, p. 207), in addition to Stanisław Vincenz, preparing to cross the border were: Lena (his first wife), Irena (his second wife), his fourteen-year-old daughter Barbara (from his second marriage), Helena Eleniak [45], and Katarzyna Pobiazyn [46].

Helena lived with Lena Vincenz in Słoboda Rungurska, while the other participants of the planned crossing remained in Bystrets. The young women did not arouse suspicion in the soldiers: thanks to their employment by the Soviet authorities, they had passes giving them the right of movement in the border zone; they could maintain contact between their two houses and collect supplies necessary for the crossing of the mountains, and through their acquaintances with border guards, orientate themselves in the current situation on the border.

The author mentions in “Dialogues” (p. 173) that “our friend Mrs Kasia” (Pobiazyn) warned him of tightened surveillance on the border by Komsomol detachments. Thanks to her connections at the post office, Helena Łuczyńska was able to inform Lena Vincenz by telephone of the upcoming crossing. Lena travelled from Słoboda to Zhabye without a pass, from where she, Kasia, and Helena reached Bystrets on foot. On the way, they were picked up by a truck, which did not arouse any suspicion. Thus all the participants in the future border crossing gathered in one place and waited for the snow to melt in the mountains.

Sunday. Bystrets – 26 May (1940) a wonderful journey, until 29 May.

“Luhy 29 May (1940) The old yoke: ‘from now on, the flights of a sparrow, tethered by a thread.’”

On Sunday, 26 May 1940, “one day the entire group left the house (in Bystrets) (…). Large windows, covered with curtains, gleamed at us from the other steep bank of the stream. ‘Why are you leaving us?’ No one saw or knew when and where we disappeared, though everyone preferred not to know, so they only whispered about us. Only the young sons of the inn owner in Zhabye (the Hertners) knew everything [47]. Later, with boyish mockery, they would ask the Soviet commanders what had happened to us. They would answer reluctantly and evasively.” (“Dialogues”, p. 174).

The Bystrets valley in May.

The group of fugitives was quite large, consisting of six people and two guides. This allowed them to take the most important notes, ethnographic records, sketches, family documents, even some books. The luggage was very heavy, but the guides helped carry it to the border, through the most difficult terrain with steep climbs.

In a letter to Józef Wilczyński dated 1 October 1959, Vincenz recalls that in writing the second volume of “On the High Uplands” he used “those notes that we carried on our backs across Chornohora, and a large parcel besides, and which reached all the way here” [48], meaning to La Combe. Also, in a letter to Matthew Stakhiv he wrote: “In my papers, carried on shoulders across Chornohora, there is somewhere a Polish translation of a chapter from that book (‘Grandfather Ivanchyk’)” (cited in Biography, p. 173), and in a text prepared for the writer on his wife’s name day we read: “Only a few years have passed since we saved on our backs the outlines, sketches, or partial fragments of the future ‘Uplands’.” [49].

As G. and T. Csorba write in their work “The Hungarian Land: Refugee Haven for Poles”, Vincenz, a lover of Dante and Homer, took with him in his rucksack “The Divine Comedy” instead of a spare pair of boots (cited in Biography, p. 211). Irena Vincenz recalls that her husband “once in Hungary, felt not only great fatigue, but also relief. He carried with him all the manuscripts, his whole world, which he knew would perish if he did not carry it on his back.” [50].

Andrzej Vincenz writes about the first drafts of “The Truth of Antiquity”, preserved “in a rucksack during the escape through Chornohora in May 1940.” [51]. Barbara Vincenz hid family photographs in her rucksack (Biography, p. 211).

When there had long been no news of Stanisław Vincenz and his family, the Soviet authorities moved his wooden house to the centre of Bystrets village and created a club there. After the Germans arrived, the Hutsuls burnt down the house. As Vincenz later learned, “the arson was not directed against me, but against the Communist club.” (“Dialogues”, p. 174). At the end of the first part of “Dialogues” Vincenz writes: “Escaping, I at least got rid of the apocalyptic boredom of Stalinism, from which I would wish to escape this globe, if it were to spread everywhere. Alas, I have lost my country as well (…). In the history of our corner of the world, preserved mainly in oral tradition, there is a story of a village headman of Zhabye, (who) wrote on a stone at the entrance to his community: ‘Here people are trusted, this is our constitution.’ (…) I often thought that the Institution from whose embrace I broke (…), should have an inscription: ‘Here people are not trusted, this is our constitution.’”

Andrzej Vincenz writes: “My parents (were) in Hungary from May 1940, where they managed to reach thanks to the help of friendly poachers.” [52].

* * *

During my stay in Bystrets on 25 June and in Slupyeyka on 3 July 2007, I heard two different accounts of the border crossing by Stanisław Vincenz and his family.

The first comes from Vasyl Mykhailovych Bilyloholovyy, aged about 75, who lives in Bystrets, in the “Pid Hadzhynov” hamlet. It was his mother’s brother, Petro Markovych Bilyloholovyy [53], who organised the border crossing by the Vincenz family. Bilyloholovyy names Jan Białostocki and Stanisław Vincenz’s sons among the participants, who are known to have crossed the border to Hungary earlier. According to him, the crossing was supposed to have taken place over the Rozshybenyk ridge. They stayed the night before the border, from where Petro returned. The following day, the fugitives crossed the ridge. The informant adds that they met a border patrol on skis and had to hide in the snow for an hour until the soldiers left. However, this story likely refers to the border crossing by Stanisław and Andrzej Vincenz on 19 March 1940.

The second account comes from Mariya Plytka-Protsyuk, aged about 75, who now lives in Slupyeyka near Verkhovyna but used to live in Bystrets, in the same “Pid Hadzhynov” hamlet [54]. According to her, Petro Bilyloholovyy (Mariya’s uncle) and Mykhailo Protsyuk (her father) helped Vincenz and his family cross the border. The crossing route passed through the Gadzhyna hollow and the top of Shpytsi. Initially, the guides themselves went to the border and prepared a shelter so that the fugitives could sleep after a difficult ascent. Petro led them into the mountains at night and left them in the shelter, having returned. Already the following day the Vincenz family crossed the border into Hungary.

It is difficult to determine which of these accounts is true. The road to Rozshybenyk is longer but more concealed, as its entire lower part, from where the road branches off to the Gadzhynska hollow, leads through the forest right up to the threshold of the lower hollow below Kizimy Ulohy. At the foot of the hollow, one can find a path leading through mountain pine thickets to a waterfall cascading down to the left. Then, by a path alongside the waterfall, to the upper hollow of Kizikh Ulohy. From here one can ascend the ridge by a steep grassy slope. On the ridge there is a path leading through the remains of First World War trenches to the peak of Munchel where there is marker 23. From marker 23/4 another path leads via a long, gentle traverse to the lake below Gutyn Tomnatyk and on to the village of Luhy on what was then the Hungarian side of Chornohora.

The path through the hollows of Gadzhyna and Shpytsi is a little shorter and perhaps more frequented (though at that time sheep were not yet taken to mountain pastures). In the lower part, it leads along a long treeless stretch [55]. This is likely a repetition, but in the opposite direction, of the route that S. Vincenz and his son took from Luhy to Bystrets on 21 October 1939.

On 20 April 2008, Professor Mirosława Ołdakowska-Kufel spoke by telephone with Barbara Vincenz-Wanders, who firmly stated that there was no overnight stay in a hut along the way. She dismissed the building of a hut as a legend spread in the Hutsul region, whose origin is unknown. She also cited the following facts: the departure from home took place at 3 a.m.; they were accompanied by neighbours Petro Bilyloholovyy and his friend Mikhtsio (Mykhailo Protsyuk). The role of the guides was limited to warning about border patrols, “for father knew this area very well.” She does not remember the path to the border because it was dark. “But I don’t think it was through Shpytsi.” There was still snow there. The guides knew the hour the border patrol passed, so everyone waited, hidden, until the patrol had gone by. At a signal, the refugees hurried to cross the border, while their guides returned home before the village woke up. They told no one about their expedition. After crossing the border “we lay down in the forest to rest, but it was impossible to sleep (sleeping on tree roots in the rain is unpleasant).” On the Hungarian side they approached the border guard. “To our horror, a lieutenant announced to us in German that he had orders to take Polish refugees back to the border. He gave us six soldiers to guard us (…), who signaled with gestures for us not to be afraid. They escorted us for a short distance, fed us, and showed us the way to a village where no one could meet us. We will never know if the lieutenant knew about it and only pretended to be a law-abiding officer. We spent the night in an abandoned mill near the village, and the next day went to the railway station and took a train to Hungary.”

Irena Vincenz, quoted in an article by Bronisław Mamoń, also asserts that the crossing into Hungary lasted three days without rest or sleep, and likewise makes no mention of staying the night in a hut.

Combining these data with the chronology at the beginning of this article and information provided in the Biography (pp. 209–210), a hypothetical schedule of the march can be established with a high degree of probability:

26/27 May. Departure from Bystrets at 3:00 a.m. Crossing the border.

27/28 May. Rest in the forest in the rain. Encounter with the Hungarian patrol.

28/29 May. Overnight stay in a “mill”. Reaching Luhy.

The distances covered each day seem very short (except for the first day), but considering the health and physical capabilities of the Author and the lack of preparation of other participants for trekking in difficult mountain terrain, they are acceptable. On the basis of this chronological schedule, the facts presented in the Biography can be considered and critically evaluated.

The time of departure from home in Bystrets is given differently in various accounts. Vincenz himself in “Dialogues” (p. 174) indicates the approximate time of departure as “after noon.” In two other accounts (Mariya Plytka and Helena Łuczyńska) it takes place at night. The author mentions their final departure from home: when they were already on the other side of the stream, “the windows, hung with curtains, gleamed at us.” Could this phrase mean night-time? However, Vincenz further writes that after their departure, suspicions arose that the whole family had been kidnapped and deported at night.