In August, our colleagues from the ‘Carpathian Society’ (Towarzystwo Karpackie) carried out a local history expedition aimed at reaching the most remote corner of the Hutsul region—the area lying south of the Chivchyn Mountains and the Hryniava uplands, right by the Romanian border. It is here, where the sources of the Black and White Cheremosh are hidden in the ravines, that the Hutsul epic refers to as the ‘Navel of the Earth’.

The ‘Navel of the Earth’ at the Sources of the Two Cheremoshs

Due to its distance from villages, lack of roads, and proximity to the border, this territory remains depressed in terms of economic development and is difficult for travellers to reach. Nonetheless, it still hides a great natural and historical heritage, preserved in our time by two national nature parks: ‘Verkhovynskyi’ and ‘Cheremoskyi’.

‘Every land … has its own navel. The furthest wedge of the desert Verkhovyna, a mountain knot that spread radiant mountain ridges around itself, formed from the oldest primeval rock layers, … is called Palenytsya. This is a rose of the winds, and also a rose of the waters. From this corner they seep out to all directions of the world: to the southwest, the sources of the Vaser; to the east, the sources of the Siret and Perkalaba; and to the north, the sources of the Cheremosh.’

Stanisław Vincenz, ‘On the High Uplands’, Book II ‘New Times — Discord’

The expedition aimed to conduct scientific observations and subsequently promote the natural and historical-cultural monuments of the Hutsul region across the European Union. it was carried out in partnership with the ‘Verkhovynskyi’ National Nature Park, the ‘Hutsulshchyna’ Society, and EGO ‘Green World’.

The journey's route through the Vizhnytsia district of Bukovyna included the regional capital, the town of Vizhnytsia, the town of Putyla, the settlement of Selyatyn, the village of Shepit, Mount Tomnatyk, the village of Sarata, Mount Yarovytsia, and the village of Nyzhnii Yalowets. In the Verkhovyna district—the village of Holoshyna, the village of Perkalaba, the klauza (dam) on the Perkalab stream, the Fata Balnului Pass, Mount Hnitesa, the Palenytsya mountain plateau, and the village of Perkalaba, with a return to Selyatyn, Verkhovyna, Iltsya, and finally the villages of Dzembronya and Bystrets.

Public transport can reach here really only from Chernivtsi. The road to the village of Shepit, through Putyla and Selyatyn, is covered by the Chernivtsi regional bus in five hours. However, thanks to vehicle support from colleagues at the ‘Verkhovynskyi’ National Park, our travellers were able to reach their destination much faster.

And so, a stop at the village of Shepit (historic names: Shypit, Shypit na Suchavi), through which the border with Romania now runs. Practically in the very centre of the village lies an interesting natural monument—the ‘Suchava Huk’ waterfall, shaped as a cascade with three ledges and a total height of five metres. in Shepit, one must also not miss the wooden St Elias Church, which has protected status as an architectural monument of national significance.

The church was built as far back as 1898 on a hill in the northern part of the village—entirely from wood, on a stone foundation. this is how it looked in the past.

Several traditional Hutsul cottages roofed with shingle still survive in the village; these are no longer frequently seen across our Carpathians.

Further travel from Shepit into the mountains is possible only by an off-road vehicle, a mountain bike, or on horseback—or on foot, naturally. our travellers reached the mountain range of Tomnatykul quickly and easily in off-road vehicles.

Here, atop Tomnatyk (1565 m), one can still observe the remains of the former Soviet radar station for anti-aircraft defence, ‘Pamir’—huge spherical radars that now look like the remnants of fantastic extraterrestrial visitors. a picturesque panorama opens from the peak: to its north stands Yarovytsia, and to the south, the peaks of the Rodna Mountains in Romania are visible.

After descending Tomnatyk, the group headed on foot toward the semi-deserted village of Sarata; now only a few resident families remain there. The village is noteworthy for its wooden 19th-century Church of the Nativity of John the Baptist. Also preserved here is a mass grave of more than two hundred soldiers who died in the First World War.

This was followed by an ascent to Yarovytsia peak (1574 m) and a visit to the village of Nyzhnii Yalowets (historic name, inexplicably changed in 1946—Nyzhnya Yalovychora). The village stretches through the valleys of the White Cheremosh and Yalovychora rivers and currently looks almost deserted. here one can view the late 19th-century wooden St Demetrius Church. There is a small waterfall on the Yalovychora stream just past the southern outskirts of the village.

Near the village, at an altitude of about 1100 metres above sea level, lies Lake Hirske Oko (also known as the Bukovinian Eye). On its shore, the travellers enjoyed a romantic dinner by the fire, sitting out until midnight and sleeping soundly under the ancient spruces.

The next day, the journey continued into the headwaters of the White Cheremosh, where in the Preluchnyi area on the Perkalab stream, the remains of a klauza (a catchment dam) were preserved—a unique hydraulic structure used extensively in the 19th and 20th centuries to collect water and float log rafts down mountain rivers. to this day, only a few klauzas survive—partially and as ruins—in the Eastern Carpathians. apart from the one mentioned, there are the Lostun and Baltahul dams (on the Black Cheremosh), as well as Chorna Rika (on a tributary of the Tereblya in the Beskids). Perkalab Klauza was considered the largest in terms of its catchment volume. built in 1879, it was named the ‘Sluice of Crown Prince Rudolf’ in honour of Emperor Franz Joseph’s son. Timber harvested at the headwaters of mountain streams was floated along the White Cheremosh to Usteryky, then by the Cheremosh to Kuty and Vizhnytsia, and onwards along the Prut to Chernivtsi and as far as Galați.

Over a century and a half of history, the Perkalab dam has suffered destruction from many floods, but some of its elements still stand. unquestionably, it is a remarkable historical heritage site, albeit rare in modern times.

The pinnacle of the society's August journey was the ascent to the Palenytsya plateau and the climb of one of the Chivchyn mountain peaks—Hnitesa (1766 m). Palenytsya is considered the highest and largest high-altitude meadow (polonyna) in the Eastern Carpathians. all around it, springs are born which form the sources of the Black and White Cheremosh, as well as the Vaser and Vișeu rivers, which flow in different directions already on Romanian territory. not surprisingly, this mountain region acquired its ancient name Bila Hora (White Mountain) in the oral Hutsul epic and assumed the sacred symbolic meaning of the ‘Navel of the Earth’.

‘The only human traces, historic, or rather prehistoric, in the vastness of Palenytsya are the mountain paths, preserved only as much as the placement of the mountain ridges permitted. whichever way you go, you will not reach permanent human settlements sooner than in two or three days. You will not hear clocks or historical pendulums there. The silence of the mountain depths and the heart of the forests does not even permit a strong wind. the only pendulums are the rhythms of noises between the whispers of spring droplets awakened from under the ice, and the summer roar of the waters; they are the rhythms of the shots from the crackle of spring ice to the summer thunder. from Palenytsya, the winds are born, the rivers are born, yet there are no rivers and winds there. it politely allows only its own children, the Palenytsya streams and breezes born in this place, to play. It is an egg within the shells and membranes of many eggs. it is that core of the Verkhovyna, squeezed by many layers of mountains and pastures, which the mountain sages secretly named for themselves the “Navel of the Earth”.’

Stanisław Vincenz, ibidem.

Mount Hnitesa (also pronounced Gnatasya) rises at the extreme southern point of the Ukrainian Carpathians, directly on the border with Romania. Thus, the expedition members made the ascent under the friendly escort of a border guard unit. from the top of Hnitesa, a mountain panorama of incredible beauty ‘for all the world’ reveals itself. other peaks of the Chivchyn Mountains can be seen to the northwest, and to the south and west—the ranges of Ineu, the Rodna Alps, Toroiaga, Petros, Fărcău… one could contemplate this beauty endlessly, and stay here forever, if not for the heat and thirst—Hnitesa has no springs, which is a drawback. furthermore, the southern and western slopes of the mountain have suffered significantly recently from low water—in August, the berry patches completely dried up and crumble to dust underfoot. fortunately, however, there are still no signs of tourists here in the form of litter and roads destroyed by cars—which is a blessing.

‘It is not so difficult to guess when we remember what a navel is: a trace of true communion, the last visible link in a closed chain of mothers, grandmothers, clans, and ancestors. Who then can grasp, who and how can untangle this tree of umbilical cords with roots reaching to heaven—the tree that released its first sprout from the womb of the first mother? A navel is a place, even if only a point, at which a tip flying from infinity and vanishing into infinity, has cut through something closed, finished...’

Stanisław Vincenz, ibidem.

Remember the Fallen, Care for the Living

The return from the Chivchyn Mountains to the lowlands was relatively swift and pleasant—again thanks to the vehicle provided by the national park—if not for the frequent stops at border checkpoints and the sight of coiled barbed-wire fences separating us from the EU border.

The contrast between the freedom of winds and waters and the lack of freedom at the border seemed altogether too striking…

Along the way, we stopped in Selyatyn, formerly a historic small town. here, two monuments of sacred architecture are preserved: the wooden Church of the Nativity of the Mother of God, dating from the 17th century, and the stone 19th-century Church of St Vladimir.

Unfortunately, local history sources for the most part ignore the existence of another historical heritage site—a large Jewish cemetery, and it is very well preserved in Selyatyn. prior to the tragic events of the Holocaust, a large Jewish community lived here, comprising about half the town’s population. today, only the headstones preserve their memory; but it behoves people to remember as well, if they wish to avoid the repetition of such tragedies…

Then the journey moved to the Black Cheremosh basin. In the centre of Verkhovyna, where we made the next stop, the somber alley of portraits of fallen defenders of Ukraine grows year by year; there are currently dozens of them. Our Polish friends took note and decided they could not simply walk past the place of memory. money was immediately collected, a basket of flowers and ribbons in the national colours of Poland and Ukraine was ordered from a local shop.

Note—this was a spontaneous, effortless, unplanned, and sincere expression of human compassion; proof that people perceive our pain as their own. it is worth valuing and remembering this…

In the next two days, the travellers also visited the graves of fallen Ukrainian soldiers at the cemetery in Bystrets—they stood there in contemplation, bowed their heads, and read a prayer. The local heroes Stepan Potyak, Volodymyr Vatuychak, and Mykola Budzanovych have found eternal rest in the Bystrets village cemetery.

The ‘Carpathian Society’ expeditions are not just for traveling and observing. often, they are accompanied by active volunteering. This was the case this time—in the village of Iltsya, near Verkhovyna, we heard that during a recent storm, a large branch of a century-old poplar had fallen onto the fence of the mass grave of the Zhabye Jews who were shot here in December 1941.

Mariya Atamanyuk, a teacher at the Iltsya Lyceum, continuously looks after this headstone memorial along with her pupils and students, for which she deserves a deep bow of gratitude. So that day we tried to help Ms Mariya in any way we could.

Together with Mariya Dmytrivna, we also viewed the forgotten remains of the Jewish cemetery in Verkhovyna-Slupyeyka. A tombstone in Iltsya and several matzevahs in the cemetery mentioned are all the material records of the once large Jewish community of Zhabye.

Naturally, we also did not miss the grave of Fr Sofron Vytvytsky (1819–1879), a pastor, ethnographer, writer, educator, and spokesman for inter-ethnic harmony in Galicia, who for a quarter of a century served as the parish priest of the local Holy Trinity Church.

By doing so, once again the testament from his famous carol was fulfilled:

Нас пам’ятайте, Нас не забувайте,

Чи то в щастію - в гаразді,

Чи в недолі, чи в журбі!

A Visit to Vincenz

The next stops on the journey were the villages of Dzembronya and Bystrets. here, for the last two years, a charitable project has been underway to renovate the place where Stanisław Vincenz’s house once stood—where, indeed, his creative idea for writing the ‘On the High Uplands’ tetralogy was born. in 2024, the memorial ‘Vincenz Cross’ was restored in the Skarby hamlet of Bystrets. this summer, a fence around the cross was made by local craftsman Vasyl Slaviichuk based on a project by architectural professor Włodzimierz Witkowski of the Łódź Polytechnic.

On the penultimate day of the expedition, the group set off from Dzembronya for the Cross in Bystrets for a traditional ‘Vincenz gathering’—over Stepaniv hill and through the Kosharishche mountain meadow. from the meadow, there is a magnificent—perhaps the finest of all—view of Chornohora. almost all the Black Mountain peaks lay before you, from Smotrych and Pop Ivan to Goverla. one’s breath is taken away every time one contemplates this grandeur and beauty!

Sadly, year by year, it is noticeable that on the luxurious Kosharishche meadow, people mow and graze less and less. at the same time, tourist ‘civilisation’ (anti-civilisation?) is intruding more actively. the most striking is the spontaneous construction of roads to new buildings and the rapid soil erosion caused by this.

Local authorities who tolerate this impropriety should be reminded that part of the national legislation of Ukraine includes the Carpathian Convention and the Sustainable Transport Protocol thereto. accordingly, the parties—recognising that Carpathian ecosystems are especially vulnerable—must take measures to promote the development of sustainable road transport and preserve traditional landscapes when constructing transport routes. what we see now on Kosharishche (and in many other Carpathian locations) is not an example of sustainable transport management. if the authorities and communities have forgotten about the principles of sustainable development by neglecting its environmental factors, soon—after the very first rain flood—the Mountains themselves will close these wounds on their body, which we currently call roads…

The Skarby hamlet in Bystrets did not get its name without reason (it means ‘Treasures’). reaching it is like arriving on another planet with different air, different sounds and colours. it is green and fresh as nowhere else. city bustle and even the war seem very distant. everything here is truly precious. it is impossible not to fall in love with this place. little wonder that Vincenz wished to be buried here: ‘Cows will still graze in the cemeteries; let cows walk faithfully by my grave too, as a green banner sways!’

This is how the memorial site of the ‘Hutsul Homer’ looks today. according to one of our colleagues, ‘from now on the most Hutsul cross and the most Hutsul fence will stand in Bystrets’. the funds to complete this work were collected by citizens of Poland who value the work of Vincenz—who also clearly understand the importance of maintaining friendly relations between our peoples, especially in times of war.

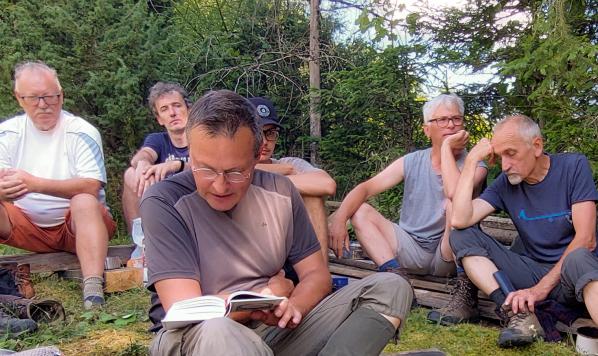

Following tradition, the reading of pages of ‘The Uplands’ took place under the ‘Vincenz Cross’.

‘How is it that Palenytsya is the knot of special and permanent connections between mountain layers, subterranean waters, and the air with its currents, winds, and clouds? In the Navel of the World, does not the earthly pulse beat, one of those that makes the earth pull more obviously in some places than others? this knot does not just catch, accumulate, and bind heaps of clouds which gather densely above it as if another mountain range. As a pulse of attraction, the Navel of the World—Palenytsya—is also an exquisite workshop of a thousand hands, which surrounds itself with its own dome, its own air—so filtered into especially light and flexible layers, and because of this exceptionally sensitive, receptive, and piercing—that it will be able to unweave the thick, hairy carpets of clouds into the finest threads and fibres. With the help of a thousand nets and sieves, it can turn them into outflows of currents and forces, and eventually break up and swallow the entire ceiling of clouds, without sudden storms or major precipitation. This air is also a depression—mischievous but good—or rather a floor for dancing, so elastic that the blocky, hail clouds which emerge as blue bears upon Palenytsya sway in rosy circles, becoming increasingly incorporeal—until the thunders dissolve into nothing, into twinkling dews, until they fall, sucked in by the springs, the forest marshes, the streams. yet before that happens, more than once at sunset and before night, one can see how mountain ridges and cloud banks become like reckless lovers exchanging their light and their darkness…’

Stanisław Vincenz, ibidem.