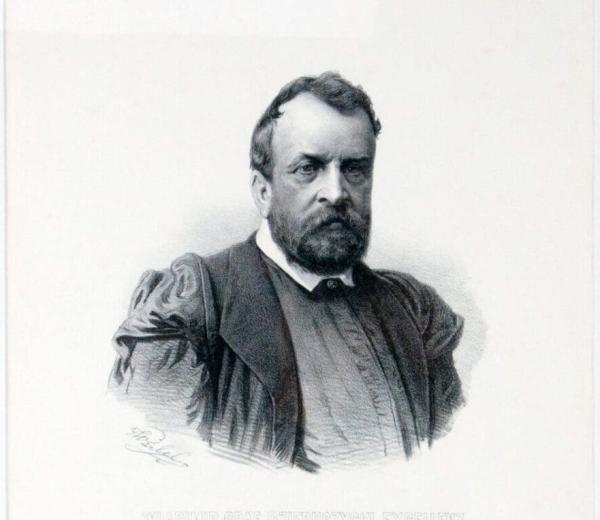

On 22 June this year, the 200th anniversary was marked of the birth of Volodymyr Dzieduszycki (Włodzimierz Ksawery Tadeusz Dzieduszycki, 1825–1899)—an extraordinary Galician naturalist, statesman, social figure, and philanthropist. He was a patron of science, museums, libraries, art galleries, exhibitions, and publications, and last but not least, a pioneer of the nature conservation movement.

Among his greatest achievements, though long neglected, can be considered the founding in 1868 of a natural history museum in Lviv (at its inception, the Dzieduszycki Natural History Museum, today the State Museum of Natural History of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine), the transfer to Lviv and enrichment of the family library and art gallery, and the creation in 1886 of one of the first in Europe, and the first on the territory of modern Ukraine, nature reserves—the forest reserve “Pamiątka Pieniacka”.

* * *

“Do not do what is not dear to you!”

The extensive noble Dzieduszycki family has been traced in the history of Eastern Europe since the 15th century. Family genealogical legend points to their origin from the Rus' boyars Dzieduszyts; it names Prince Vasylko Romanovych of Novohrad-Volynskyi, the brother of Danylo of Galicia, as the founder of the line. From the 18th century, the Dzieduszyckis bore the title of count and the Sas coat of arms, perhaps the most widespread among the Rus' nobility. by the 19th century, their estates were scattered across the borders of three empires: the Habsburg, Hohenzollern, and Romanov.

According to family tradition, the historical mission of the Dzieduszyckis was seen as serving society and devotion to one’s beloved work. this was reflected in the family credo: “Non facere aliquid quod non placet tibi!” (Do not do what is not dear to you!)

The life of Volodymyr Dzieduszycki can be considered a vivid embodiment of this maxim, and he himself was perhaps the most prominent representative of his family in the 19th century.

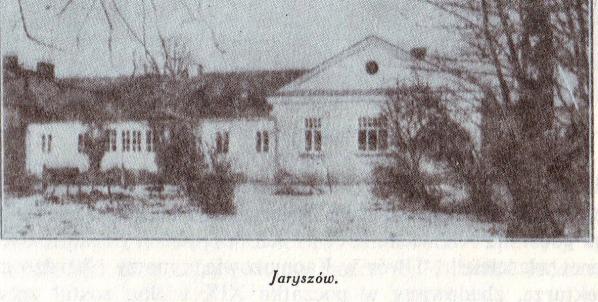

Volodymyr was born in Eastern Podillya, in the town of Jaryszów in the Mogilev district of the Podolia Governorate, where one of the Dzieduszycki family estates was located at the time.

The photo shows the Dzieduszycki manor in Jaryszów. The house was destroyed in the revolutionary year of 1917.

He spent his childhood in the villages of Poturzyca near Sokal and Zarzecze near Jarosław, as well as in Lviv, where the family moved for the winter.

The palace in Zarzecze (Podkarpackie Voivodeship), which currently houses the Dzieduszycki Museum.

His father, Józef Dzieduszycki (1772–1847), was a highly educated man, a patriot of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and a comrade of Tadeusz Kościuszko in the 1794 uprising. He established a research library in his Poturzyca estate, which contained 20,000 books and manuscripts, some dating back to the 16th century.

Włodzio, as he was known in the family, received his early education from private tutors, who included such famous figures as the poet, geographer, and local historian Wincenty Pol; the founder of the Lviv University botanical garden, Prof. Jan Jacek Łobażewski; the ornithologist Ernst Schauer; the director of the Lviv University library, Franciszek Stroński; and the philologist and historian August Bielowski.

Volodymyr Dzieduszycki never disavowed his ethnic (Rusyn) roots. His own children later recalled their father often saying: “I am not actually Dzieduszycki, but Didukh.” He defined his ethnic and political identity with the concept of “of the Rus' line, the Polish nation” (gente Ruthenus, natione Polonus). This form of self-identification was quite common among the Galician nobility and intelligentsia. it took shape in the late 18th and early 19th centuries to denote Polish patriots of Rus' origin. The historical basis for this was a stereotype of the Rus'-nobleman established in the Commonwealth, in whose consciousness a firm sense of his Rus' ethnic origin and kinship with “our Rus'”, “our Rus' people” was embedded, while his belonging to the Polish political nation remained unquestioned.

Volodymyr Dzieduszycki was not a bystander to the political events of his time, but politics was never “that which he loved”.

In the thick of the “Spring of Nations” in 1848, the count predictably found himself among the leaders of the Rus' Assembly (*Ruskiy Sobor*). That same year, he was elected president of the Galician Economic Society. By 1863–1864, he joined the National Aid Organisation for the January Uprising against the Tsarist autocracy, which unfolded under the slogans of Liberty, Equality, and Independence in the territory seized by the Russian Empire. It is worth noting that at the time, this concerned gaining common freedom from Tsarist despotism for Poland, Lithuania, and Rus'.

In 1861–1876, Count Volodymyr Dzieduszycki was elected as a member of the Galician Provincial Sejm, and from 1874–1878, as a member of the Austrian Parliament (Reichsrat). In 1876, he even consented to being elected Marshal of the Galician Sejm, but only for a one-year transition period. from 1884, he inherited a senator’s seat in the upper chamber of Parliament, though he largely neglected his duty to attend sessions.

His “kindred labour”, to use Gregory Skovoroda’s phrasing, lay in altogether different, non-political matters...

* * *

Dzieduszycki as an Organiser and Patron of Museum Affairs

By Volodymyr Dzieduszycki’s own admission, the creation of a natural history museum became the most precious and beloved project of his life.

As early as the 1850s, the young count began moving his natural history, art, and literary collections from family estates to the capital, Lviv. In the family palaces, these collections were available only to family members and occasional guests, while his desire was to make them public. these circumstances prompted him to purchase a two-story residential building with adjacent outbuildings at 18 Teatralna Street in 1868 and begin adapting it to the needs of the future museum.

During the reconstruction of this building, which had also suffered fire damage during the bombardment of Lviv in the 1848 revolution, it turned out that it was significantly older than previously thought and lacked even a masonry foundation. Laying a concrete foundation beneath the dilapidated residential building and the entire process of its conversion into a modern museum proved a complex and very costly task. However, the Museum was ready to be opened and stocked in short order—by 1869.

During its founder’s lifetime, the Museum had seven departments: zoological, palaeontological, mineralogical, geological, botanical, archaeological, and ethnographic. Experts compared its scientific value to that of the National History Museum of the British Academy of Sciences in London. Today, it functions as the State Natural History Museum of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine.

The Natural History Museum in Lviv, contemporary view

It is interesting that in the grandly reconstructed Museum building, the founder had a modest little room on the first floor for himself, in which he actually resided. For fear of collapse, its ceiling was supported by a small iron pillar wreathed in flowers. this corner was not only the hub of the count’s intensive scientific activity, but also a centre of the cultural, socio-political life of Galicia at the time.

Today, we find it hard to believe that this exceedingly wealthy magnate, who enjoyed universal respect and provided shelter in his estates “out of kindness” to scientists, writers, and artists without a penny to their name, or to January insurgents hiding from repression, was himself an excessively modest man in his personal needs and appearance. While distributing money with a generous hand for scientific ends, the acquisition of collections, the publication of scientific works and school textbooks, exhibitions, scholarships for young scholars and artists, and for the promotion of ethnic creative work, both Polish and Ukrainian—he modestly concealed these acts of generosity, claiming no thanks in return.

The long process of establishing the Museum culminated in 1880 with the act of handing it over to society, so that its treasures would be available for all to see. Volodymyr Dzieduszycki also provided for its lifelong maintenance from his own funds at a rate of 12,000 crowns a year; the museum was then officially named the “Dzieduszycki Natural History Museum”.

Its creator defined the significance of the Museum as follows: “Museums of this type, created and opened in cities with the standing of Lviv, concentrate local scientific forces, awaken a passion for science in student youth, and spread through visitors the knowledge and desire to study nature to the furthest corners of our native land.”

Volodymyr Dzieduszycki was also destined to become one of the main patrons and founders of science in Galicia. fascinated by the natural sciences—ornithology, entomology, botany, geology, and palaeontology—he provided financial support to many Galician natural scientists, most notably Maksymilian Siła-Nowicki and Marian Łomnicki.

Besides promoting nature conservation, V. Dzieduszycki concerned himself with legislative aspects of resource use. In 1868, together with other scientists, he prepared several bills on prohibiting the trapping, destruction, and sale of alpine animal species. with his participation in 1875, the Galician Provincial Sejm adopted a hunting law that prohibited spring hunting of birds for the first time in Europe.

Another—though not the last—of Volodymyr Dzieduszycki’s passions was archaeology. indeed, an archaeological collection was established in the Museum at its very inception. upon receiving word that in 1878, the inhabitants of the village of Michałków—located near the mouth of the Ničlava River in Podillya—had discovered a collection of prehistoric gold jewellery, the count dispatched Władysław Zontak, the general curator of the Museum, to the site. he subsequently funded the work of an archaeological expedition that researched the area and saved some of the unique artefacts from looting and being banalilly melted into gold bars. Archaeologists concluded that the find belonged to the Thracian Hallstatt cultures and dated back to the 7th–8th centuries BC.

In 1897, as a result of targeted searches near the first find, a second part of a site of a similar character and from the same era was excavated. the archaeological site at Michałków eventually came to be known as the “Michałków Hoard”.

With the permission of the imperial government, a portion of the treasure (weighing over 3 kg) was placed in the Dzieduszycki Museum in Lviv, where it remained available for study and public viewing until 1920. in the inter-war period, it was moved to the Lviv Historical Museum. in 1940, this archaeological collection was removed to Moscow, and its subsequent fate remains unknown. A part of the gold items found at Michałków, which never reached the Dzieduszycki Museum from the start and was not looted on site, is preserved today in museums in Vienna, Budapest, Kraków, and Berlin.

Scientists evaluate the “Michałków Hoard” as one of the most precious archaeological sites ever discovered in modern-day Ukraine.

* * *

Library and Gallery

In the mid-19th century, Volodymyr Dzieduszycki moved the famous Poturzyca scientific library, inherited from his father, Józef, to Lviv. shortly after, the collection of paintings by Western European authors—the “Dzieduszycki-Miączyński gallery”—inherited by his wife Alphonsina from her parents, was also transferred. effectively from 1858, the library became open to readers. Lviv scholars, journalists, and writers visited it.

Over the ensuing years, Volodymyr Dzieduszycki enriched these collections with new purchases of books and canvases, causing the library to double in size and the art gallery to contain about 800 paintings by famous authors, among whom Polish artists now predominated: Artur Grottger, Jan Matejko, Juliusz Kossak, and others.

The Poturzyca library was housed together in special additions to the Dzieduszycki palace in Lviv at 15 Kurkowa Street, near the foot of Castle Hill (now Mykola Lysenko Street).

To provide for the financial and organisational upkeep of the Museum and library, the “Poturzyca Entailment” (*Ordynacja Poturzycka*) was founded in 1893—a legally established, indivisible inheritance approved by the Parliament in Vienna.

It was Count Dzieduszycki’s dream to make the art gallery available to all visitors. this bequest was carried out after the patron’s death, in 1909, by Alphonsina Dzieduszycka, who opened the doors of the gallery “to the public, free of charge”.

At its peak, Dzieduszycki’s library was one of the richest and most valuable in Lviv. In 1939, it contained over 50,000 volumes of printed works—about 17,000 of which concerned history and literary history—334 manuscripts, 1,820 autographs of famous people (beginning with the manuscripts of Juliusz Słowacki), 3,000 engravings, and about 500 historic geographical maps.

However, 1939 marked the start of a period of loss in the history of this unique collection and the Dzieduszycki palace in Lviv. part of the library holdings were transferred to the Ossolineum (now the Vasyl Stefanyk National Scientific Library of Ukraine); some of the oil paintings went to the Lviv Art Gallery. a part of the collections moved to libraries and museums in Poland.

In 1940, the Dzieduszycki palace on Kurkowa Street was converted into a boarding school, and shortly thereafter, was handed over to a military unit. in this process, it suffered a barbaric looting.

In the post-war era, the building was transferred to the jurisdiction of the USSR Ministry of Defence. in 2009, it passed to the Security Service of Ukraine. obviously, the palace is not currently open to the public; it is therefore difficult to say in what condition it remains.

To this day, the holdings of the Dzieduszycki Library and its collections remain scattered among various institutions and private archives in Poland and Ukraine.

* * *

“Pamiątka Pieniacka”

In the 1880s, Volodymyr Dzieduszycki set aside a unique area of primary beech forest in the Peniaky estate—located on the main European watershed in the Brody district of the Zolochiv circuit of Galicia—declaring it a reserve and placing it under protection “for all time”.

The photo shows the Dzieduszycki estate in Peniaky; mid-19th-century lithograph.

This forest massif was all the more precious because in those times, many White-tailed Eagles (*Haliaeetus albicilla*) nested in the crowns of the 200-year-old giant beech trees—representatives of an endangered species of raptor, the largest in all Eurasia. Let us note that from beneath that Peniaky forest flows the right tributary of the Seret River, the largest waterway within the modern-day Ternopil region, which feeds the considerable Zalozhci and Ternopil ponds and empties into the Dniester below Zalishchyky.

The act of establishing this nature reserve was formalised in Vienna in 1886 by a resolution of Parliament, and the 22.4-hectare reserve itself was named “Pamiątka Pieniacka” (the Peniaky Monument).

It is important to note that Dzieduszycki did not create the reserve for forestry management, hunting, or for any other utilitarian goals—not even for religious reasons. its creation pursued solely the goal of preserving natural heritage as a value in itself, and also as a base for scientific observation.

The founding of a nature preserve with a conservation regime of absolute wildness was a historical precedent for Galicia at the time, if not for the whole of Eastern Europe.

Consequently, today Volodymyr Dzieduszycki can with confidence be considered a pioneer in the matter of formal nature conservation in modern-day Ukraine! and 1886 the birth-year of formal nature conservation in our homeland!

Though an opinion persists both among the public and in certain scientific circles that “Askania-Nova” was the first reserve in Ukraine. let us clarify nonetheless: that steppe reserve was created by Baron Friedrich Falz-Fein on the initiative of the botanist Józef Paczoski only in 1898—twelve years after Count Dzieduszycki had placed “Pamiątka Pieniacka” under protection.

In the early 20th century, scientific research into “Pamiątka Pieniacka” was carried out by the prominent botanist Władysław Szafer. In 1912, following the death of the reserve's founding father, he published a pioneering study of its flora (Szafer W., 1912. *Pamiatka Pieniacka* // Sylwan, No. 30).

In this work, Szafer established the exceptional value and the necessity of preserving “Pamiątka Pieniacka”, and concluded with these words: “…Whoever finds themselves within the forest ‘monument’ in Peniaky, in the forest twilight of the ancient beech forest, will deeply feel the charm and beauty of primeval nature… Let him reverently remember the name of the man who first sensed the beauty of this corner of the land and handed down ‘Pamiątka Pieniacka’ to future generations.”

Regrettably, it was not possible to pass down “Pamiątka Pieniacka” to future generations in all its natural richness and beauty. in the subsequent century—with its two world wars and its practice of unrestricted consumption of natural wealth—the fate of this unique primeval forest proved sad. In the First World War, “Pamiątka Pieniacka” was heavily damaged; after the Second World War, it was logged out completely.

However, many forest areas closely related in species composition to the former “Pamiątka Pieniacka” survive to this day on the low-mountain ridges of Voronyaky and Holohory adjacent to this area. only, naturally, you will no longer see 200-year-old becches or White-tailed Eagle nests there today.

Contemporary view of the surroundings of Peniaky. Photo by the author.

Today, the “Pivnichne Podillya” (Northern Podillya) National Nature Park carries out the mission of researching and protecting natural heritage in these parts. by the way, the original name of the proposed national park was in fact “Pamiątka Pieniacka”. It was with that name that the project was submitted by its developers to the Ministry of Environmental Protection of Ukraine. However, during the stage of approving the content of the relevant Decree of the President of Ukraine creating the park, it was changed—for political reasons. Or if we are being frank—changed as a result of a petty political intrigue.

* * *

Volodymyr Dzieduszycki and the Hutsul Region

Less well known is Volodymyr Dzieduszycki’s interest in the historical, cultural, and natural heritage of the Hutsul region. this was manifested in his invitation to Volodymyr Shukhevych, then still a student at Lviv University, to participate in stocking the collections of the Dzieduszycki Museum. at Dzieduszycki’s request and expense, Shukhevych worked throughout the 1870s seeking and collecting samples of traditional Hutsul everyday culture that could be of value to the museum.

On V. Dzieduszycki’s initiative, V. Shukhevych also participated in the organisation of provincial ethnographic exhibitions in Ternopil and Kraków (1887), creating a separate Hutsul section at them based on the holdings of the Dzieduszycki Museum and his own collections.

Also little known in Ukraine is the fact that the multi-volume ethnographic edition of Shukhevych’s “Hutsulshchyna” was published in Polish almost immediately after the Ukrainian version, through the patron’s support of the Dzieduszycki Museum.

V. Shukhevych’s work in Polish appeared in 1902, 1904, and 1908. unlike the Ukrainian version, the author divided the Polish edition into volumes rather than parts. There were four volumes in all: the first volume covers the first two parts of the Ukrainian edition; subsequent volumes correspond to the parts of the Ukrainian work.

While V. Shukhevych dedicated the Ukrainian edition of “Hutsulshchyna” to the memory of his parents, the Polish version was dedicated to the memory of V. Dzieduszycki.

It is also worth noting that Shukhevych was assisted in collecting materials for “Hutsulshchyna” by numerous correspondents from the region: Oleksa Volianskyi, Luka Harmatii, Teofil Kysylevskyi, Ivan Popel, Yaroslav Okunevskyi, Mykola Koltsuniak, Petro Dodiak, Klementyna Lysynetska, Dmytro Yendyk, Petro Shekeryk-Donykiv, and many others.

For a century, Shukhevych’s “Hutsulshchyna” has been a valuable source of local lore for many ethnographers, naturalists, writers, and tourists.

* * *

Recognition and Commemoration

During his lifetime, Volodymyr Dzieduszycki’s scientific and philanthropic merits were highly appreciated. He was a corresponding member of the Kraków Academy of Arts and Sciences, an honorary doctor of philosophy from Lviv University, an honorary member of the Copernicus Society of Naturalists in Lviv, the Poznań Society of Friends of Learning, the Pedagogical Society in Kraków, the ornithological societies in Altenburg, Vienna, and Berlin, the Natural Science Society in Dresden, and the Geological Society in Vienna, among others.

From 1877, he held the title of honorary citizen of Lviv, and later of Brody, Sokal, and Kolomyia.

The 200th anniversary of Volodymyr Dzieduszycki’s birth was not, alas, commemorated at the highest state level, either in Ukraine or in Poland.

Nonetheless, by decision of the Podkarpackie Voivodeship authorities, 2025 was proclaimed the “Year of Volodymyr Dzieduszycki”.

In Ukraine, OUR illustrious compatriot was remembered as well. Over the course of the year, at the Vasyl Stefanyk National Scientific Library in Lviv, the State Natural History Museum of the NASU, the “Pivnichne Podillya” National Nature Park, and the Ukrainian Catholic University, a series of meetings, scientific conferences, seminars, lectures, and exhibitions were held dedicated to the life and legacy of Volodymyr Dzieduszycki, and to his scientific, museum, philanthropic, and social activity.

The photo shows jubilee celebrations in Zarzecze.

Finally, coinciding precisely with the birthday of OUR honouree, 22 June 2025, large-scale celebrations took place in his native village of Zarzecze (Jarosław County, Podkarpackie Voivodeship, Poland), where the Dzieduszycki Museum currently stands.

In the Armenian Cathedral of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary on Virmenska Street in Lviv, a divine liturgy was held on this day to mark the jubilee.

Representatives from both Ukraine and Poland jointly participated in the aforementioned anniversary celebrations. Indeed, the heritage of Volodymyr Dzieduszycki belongs to both our nations; it brings us closer and enriches both us and our Polish brothers.

One wishes to hope that the ice of oblivion surrounding the name of Volodymyr Dzieduszycki and the colossal legacy of his life is finally breaking. That not all is yet lost or scattered across distant worlds. That future generations will eventually learn everything, and that all distinguished individuals will be given due honour—according to their works and the fruits of their labour.